blog

Welcome to my blog. This is a place where I think out loud, show you what I’m up to in the studio, share impressions of inspiring events or everyday moments that moved me. Some entries are carefully curated essays, others are just a few thoughts, sometimes written in English and sometimes in German.

Featured posts

newest blog entries:

Aninka: A handful of memories

Without too many words, I’d love to evoke the image of my aunt and godmother Aninka Harms today. Ten years ago, an accident ripped her from this world, and she remains frozen in time, forever the 49-year-old she was, forever never aging.I looked back to some early photographs, trying to find images that capture the way in which she influenced me. While I would certainly have become a creative soul with or without her, I’m sure that she encouraged me in my creative unfoldment and even influenced me significantly on my jewellery path.

Without too many words, I’d love to evoke the image of my aunt and godmother Aninka Harms today. Aunt, jewellery designer, artist, baroque violist, mother, wife, creative soul. Ten years ago, an accident ripped her from this world, and she remains frozen in time, forever the 49-year-old she was then, forever never aging.

I looked back to some early photographs, trying to find images that capture the way in which she influenced me. While I would certainly have become a creative soul with or without her, I’m sure that she encouraged me in my creative unfoldment and even influenced me significantly on my jewellery path. This here is by no means a complete picture; on the contrary, it’s a very scewed one, just a scattering of memories for the occasion.

Aninka was such a complex and multifaceted person, like one of those new artsy cut gemstones: asymetrical, glittering, beguiling, beautiful, caught in mid-dance, yet with unknowable depths and hidden facets too.

This photograph above must have captured one of our very first meetings. It’s a whole story: Me keeling over, having sat, unsteadily, just a second before, wedged in a corner of our horrible brown corderoy couch. Then the milky stain, my crocheted slippers, her keen interest, neck outstretched. Here, she is not even thirty, just starting out her career as a free-lance jewellery designer in Salzburg.

Here we are, on my very first visit to Europe at 18 months. It was summer, some time before my brother was born, when I basked in the world’s attention. Aninka is all curls and movement and crinkly laughter.

Above, another summer visit to Europe, a bit later, when I was in second grade. Now, Aninka and her then-husband Hans had moved to Munich. The sisters - my mother and Aninka - saw each other seldomly, their lives on separate continents. A visit was all the more intense then, after many months if not years of not seeing each other. Here we all are - my brother, my cousin, Aninka and myself - crammed into her bed with morning coffee and cocoa in hand-made cups. It’s an impressive array of different hairdoes, with my brother’s being the most normal.

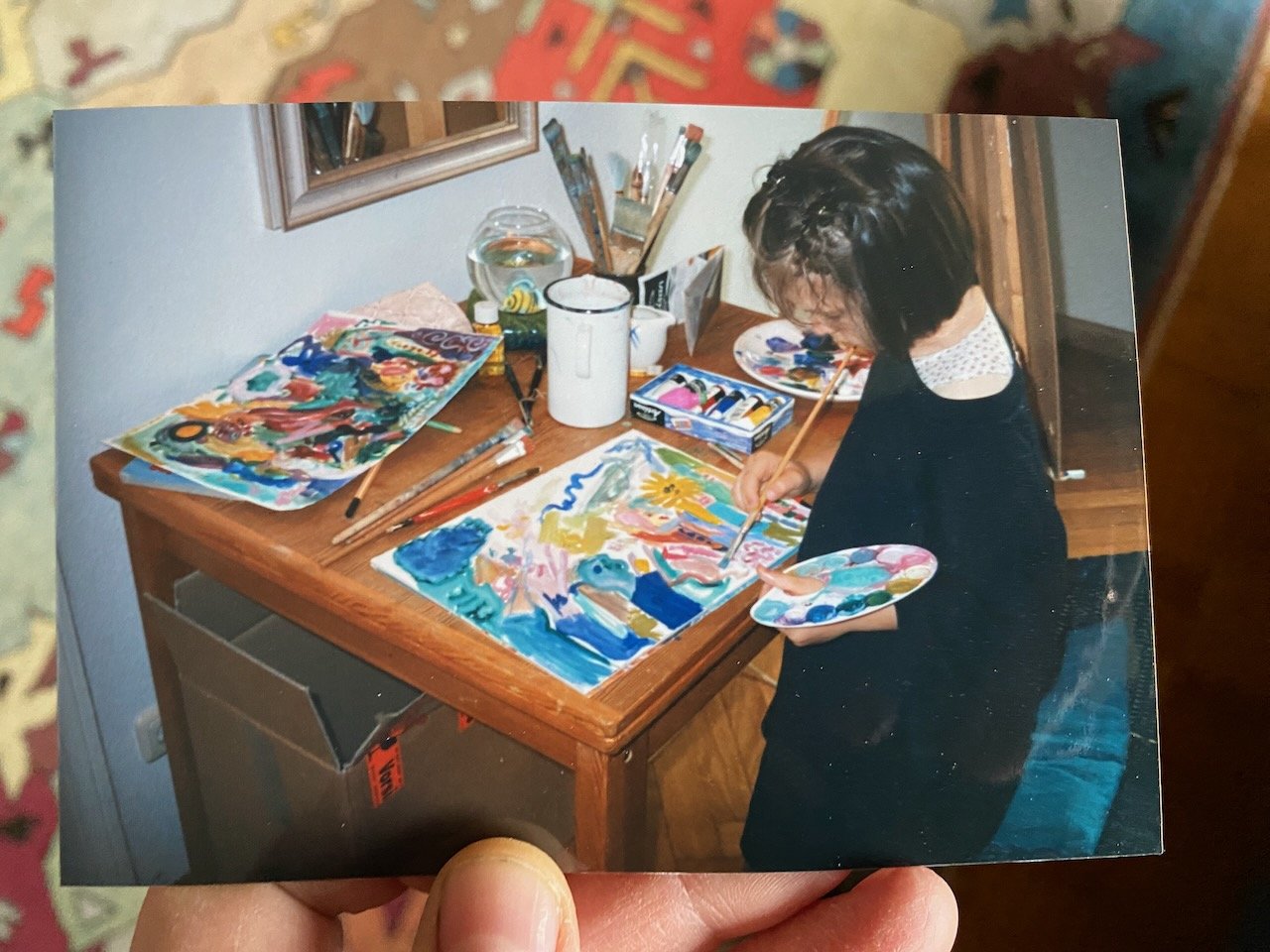

On that same visit, Aninka gave me my first oil paints, and apparently I am unstoppable here, way past my bedtime, painting in my nightgown covered in an old over-sized t-shirt of hers for protection. This was in her flat in Munich in Baaderstraße; I still remember the high ceilings, the long passageway, the wooden floors treacherous with splinters.

Here, above, is another thousand-word-photograph: The abundant floral arangement from my grandmother’s garden, Aninka painting with watercolours, apparently critical of her own work; my brother and me trying to paint as well, my face a mixture of admiration and envy, serious, with that high fringe so long before it became fashionable. My brother is holding his paintbrush in the special pen grip he had developed for himself during that time, which his kindergarden teachers eventually drummed out of him.

Here, just a scattering of memories, snapshots, frozen in time. While Aninka and I certainly had our disagreements and painful moments later on, she did inspire a sense of excitement and awe around art and jewellery and all things beautiful in me. Tonight, quite grateful, I raise a glass to her, my very own fairy godmother.

My Otherbirthday

To say that those initial six months changed me is a gross understatement. The experience distilled my life in an instant, it filtered out a lot of bullshit. It is the single best thing that has ever happened to me in my life so far.

I think for my tenth anniversary it’s worth delving into the details of what this experience brought to life, got rid of, and how it has shaped my life for the better. Here are some of the thoughts I became aware of, as I dug deeper, and some of the learnings I took from it.

My Otherbirthday

Today I am celebrating my tenth otherbirthday. A day that’s been a silent private celebration up to now. It’s probably more important than my conception or my actual birthday, when I came into being, because out of this experience I am beginning to extract my purpose.

Written in English.

Today I am celebrating my tenth otherbirthday. A day that’s been a silent private celebration up to now. It’s probably more important than my conception or my actual birthday, when I came into being, because out of this experience I am beginning to extract my purpose. Despite its significance, I have never written about my otherbirthday in much detail publicly.

To be honest, I never had the right words to write about it. I’m not sure I have them now, but the time feels appropriate to share something so personal. We don’t only need to allow more emotion into our worlds, we need to learn to hold our emotions, those of others, to open up, and allow ourselves to be changed and weathered by our circumstances. To me, those who have lost their ability to be moved in life are somehow calcified by bitterness and disappointment, and need a good rinse of joy, like my coffee machine every couple of months.

On this day, ten years ago, I woke up in an ICU ward with no less than seven tubes stuck in my body. As I slowly drifted into consciousness, I became aware that I was incredibly thirsty; there was nothing but thirst, my world was thirst, the scratchiest sand-paper deepest desert thirst you can imagine, but I couldn’t make a single sound to cry out for water because there was a tube stuck down my throat as well.

I was edging back into a kind of awareness of my surroundings, although my vision was blurry with morphine. Ever so slowly, fragments of memory returned. I was waking up from an eight hour shoulder surgery, where an expert team of doctors had cut out my entire left shoulder joint and part of my left humerus, along with a sizeable tumour that had been growing there. They had replaced the bone with an artificial titanium shoulder joint. As I learned later, the procedure had been a little more complicated than anticipated (which was difficult enough); three separate lung emboli had forced the doctors to resuscitate me repeatedly, while I was losing grotesque amounts of blood. It must have been a serious eight-hour battle for those doctors to keep me alive, and I’m grateful to have been unconscious.

Before the operation, I had collected blood from seven different friends and family members who happened to share my blood type: Altogether 5,5 litres of that ultimate talisman, that mythical life force which I imagined flooding my body with their will-power, their strength, their tenacity, their complex love for me.

February 2011, the night of my twentieth birthday. A preciously fierce snapshot showing next to one of the kindest and most beautifully brittle souls I know, dear Louis.

About three months before, in November, just days after my last exam marking the end of my first year at university, I had been diagnosed with an aggressive, fast-growing type of bone cancer in my left shoulder joint and upper arm. An invasion of needles, medicines, poisons, facts, fears, fictions, hopes and strange odours followed. The boundaries between “good” and “bad”, and between “mine” and “not mine” dissolved quickly; the chemotherapy was good because it killed those rampant cells mercilessly, but it was also killing other fast-growing cells. “Cytotoxic,” it said on neon yellow stickers on each gelatinous bag dangling from my drip stand. I lost my hair. It didn’t matter. I lost my teen chubbiness, fifteen kilos in two months, which felt fantastic. I lost my appetite for food, my ability to concentrate, to work towards a larger goal. I lived day by day, eternally grateful for the neat slicing of time into mornings and afternoons and evenings, marked by sunrises and sunsets; a light-filled morning offers a new opportunity, every time. Was I fighting a grand fight? Was I fuelled by anger and a sort of combat-energy? Not really, no. It didn’t feel like fighting anything at all, simply because almost everything took an indescribable amount of effort. To concentrate on a book was an effort, to will myself to be interested in the interestingness of life, to watch a movie, to have a meaningful conversation. I was certainly not joy-less in that time, but filling my day with anything at all was exhausting. Everything was an act of rebellion.

It was both a time of intense aloneness, because I was living through experiences I struggled to articulate to others, and also a time of the sincerest and most intimate companionship I had ever experienced. The fragility you inhabit in such a situation allows for the greatest intimacy imaginable. When you allow others to see you in that bare, broken state, that moment of trembling weakness transforms into sheer strength: When you mobilise yourself to get up from your hospital bed for a bathroom trip, drip stand in tow, and two metres across the room transform into an arduous journey, an adventure almost, stretched over long minutes, and you let someone bear witness to that struggle. I remember feeling a new sense of precious connectivity with my mother, coming back and being a child again, being cared for with so much love, after having spread my wings at university for a year.

The operation to remove the by now grape-fruit-sized tumour was scheduled for the 11th of February. A period of convalescence followed, along with a second cluster of three rounds of chemotherapy. Since 2011, I have had another three shoulder surgeries, each improving on the previous model.

To say that those initial six months changed me is a gross understatement. The experience distilled my life in an instant, it filtered out a lot of bullshit.

It is the single best thing that has ever happened to me in my life so far.

I think for my tenth anniversary it’s worth delving into the details of what this experience brought to life, got rid of, and how it has shaped my life for the better. Here are some of the thoughts I became aware of, as I dug deeper, and some of the learnings I took from it:

2011. A snapshot at my mother’s house, one of those peaceful afternoons, about two months post-op.

1. I learned about facing my fear of pain and of death.

I believe our society (at least in predominantly Western cultures) has unlearned dealing with our own deaths well. We don’t speak about it, so the subject becomes unspeakable. We are all the more afraid of it because of its namelessness. Of course, losing someone isn’t made any less emotional if death is no longer euphemized; on the contrary. But one hopes that because the tempestuous force of death is acknowledged, one is perhaps a little better equipped to face the loss of loved ones and eventually one’s own departure.

Facing my own mortality in such a drastic way mostly killed my own fear of death. The idea of losing yourself, losing that conscious thinking inner voice, of dissolving into particles, can be absolutely terrifying. Something shifted there for me which is almost impossible to articulate. It is as if an impending sense of loneliness and lostness crystallized into a feeling of belonging and togetherness, ever so gently, a feeling of being caught, cradled, and embraced by the world, a feeling of porousness where I realize that the boundaries of my conscious self and my body might not be as real as I thought.

In my life now, I don’t evade the idea of dying, and it doesn’t make me uncomfortable anymore. Death, to me, now, will be like going home. It will happen eventually, maybe sooner or maybe later, when this journey has come to its end. And I hope that it will be okay.

For many, the fear of dying is tethered to the fear of pain. We tend to be very, very afraid of pain – with good reason from an evolutionary perspective, and we do all kinds of things to avoid pain. Yet, in my experience, our fear of pain is often much more magnified than the pain itself, once we brace ourselves.

There was pain too in my post-operation experience: The kind of incredible, breath-taking pain that really taught me how powerful my mind was, that became so much part of me that I had no idea where my body ended and the pain began. I remember the first night I was truly conscious after my operation, not being able to sleep at all, spending six hours inhaling waves of pain and releasing them out my back, making myself permeable, talking to the pain, being humbled by it and awed, imagining an endless ebb and flow, a sinus wave of pain, and eventually falling into a powerful trance where I was riding these waves triumphantly. I came to conclude that there is nothing more powerful than mastering pain; it removes most fears in life.

Childhood memories, escaping into inner worlds of infinite brightness. Watercolour and ink on paper.

2. I learned how to unearth adolescent shame, and to let it go.

What this experience really did was to eradicate my shame almost completely. To understand this, I had to delve a little deeper, further back into my growing up: My late childhood and early adolescence was profoundly marked by shame – a deep, irrational, shuddering sense of shame. Not even shame about things I did, although behaviour naturally adds another layer, but shame about the way I was. Like I had somehow become this never-good-enough, squishy disgusting thing that wasn’t worth the love and attention of others.

There is no rational explanation of this; it’s just the way I began to feel about myself around the age of 11 well until I was finishing school. I was ashamed of my un-slender body and my looks, I was ashamed of being too clumsy, too greedy, ashamed of any kind of desire I might have, ashamed of being unfashionable and ashamed of my love for fashion at the same time (secretly pouring over women’s magazines), I was ashamed of how little I knew about men and love, and at the same time afraid of being “improper” if I knew more. I was ashamed of bodily things like sneezes or teary emotional breakdowns in violin lessons, which originated from the shame of not having practised enough the week before. If someone complimented me, I would find a way of being ashamed too. It was a vicious spiral trap that sucked me into ever more ridiculous cycles of self-loathing and bouts of triumphant spitefulness. Mostly, I was also ashamed of my shame.

I found solace in literature and my school work, which was interesting and offered countless alternative worlds, and which I could excel at. Above all, I found safety in my scintillating internal world, brought to life with watercolours and inks and paintbrushes, and populated by wild and colourful characters.

After my experience of facing my mortality, my trapped-ness in that sense of shame shattered like a frozen lake bombarded with rocks. It’s difficult to untangle what exactly caused that change, but I believe it brought me to the brink of humanness, a place of utter helplessness and fragility, of inner and outer limits, a place of nakedness that does not stop at your skin level but penetrates even deeper, a place of bodily fluids and tubes in weird places and strange odours that had nothing to do with me, and at the same time, everything to do with me.

The thought of having something foreign growing within me left me in an ambivalent state where I was feeding friend and enemy cells alike with every bite I took, with every ounce of willpower I mustered. The enemy was undiscernible, it was part of me.

I believe you probably have two different options in that situation.

Either you turn on your own body, you make the entirety of it your enemy, you hate yourself, you distance yourself, you feel contaminated or dirty or broken and eventually disassociate from yourself so much that you somehow give up on yourself.

Or, and this was my story, you embrace that badness in your body. Because I was able to believe – miraculously – that none of this was my fault, I was able to learn to tolerate and live with those “evil” cancerous cells. I felt a kind of empathy for my failing immune system and my own limits, my fragility and my humanity, for my breathlessness as I was climbing stairs and for my bouts of nausea. And every bit of creative work I could do became the biggest gift. By extension, I had to embrace my entire other shadow side too. I developed a strange sense of compassion for my younger self, I wanted to go back in time and hug that poor trembling-little-bird-version of my inner self and tell her how strong and beautiful she could become. And, I learned to accept limitations in others too.

I think this attitude has made all the difference – in a much more impactful way than I could have guessed at the time. I’m not suggesting that you think away your cancer. But you have to start somewhere.

2015. A search for colour, for life, for small amulets stolen from then colourful internal paradise. Photograph of my LeafEater jewellery by Lydia Schröder.

3. I learned to search for Eros.

My desire to die well implies a desire for living well too, and this question has caused me to seek out the kind of life and the kind of relationships I want to pursue. Questions and answers around what it means to lead a meaningful life have presented themselves in turn, causing me to think, rethink and revise my life on a regular basis.

Above all, I want my life to be in search of Eros – in its full, all-encompassing original meaning: life energy and vitality in all its facets. I want to feel with all my heart, I want to dance, to fill my world with vivid colour and smiles and tears; I want flowers, I want fantastic food, music, exquisite art, I want beautiful hand-crafted things to surround me, I want books filled with secret yearnings und shadowy fantasies, I want feasts and chocolate and red shoes, I want champagne and lacy underwear. I want to be in Nature and watch her petals unfurl and flourish and decay again with the seasons. I want to see achingly beautiful sunsets on my evening walks, I want to see my paintbrush dip and twirl, I want to watch my enamels melt in glorious mottled patterns. I want to write letters to people and capture a bit of that by-gone preciousness. I want gold, and delicious deep-sea-coloured gemstones and ancient myths in my life. I want to work hard and be tired at the end of my day, I want to sweat, and laugh until my sides hurt.

With my partner, I get to pursue a precious romantic partnership where we both truly own our desire for each other: It’s a multi-faceted bouquet of love, made of stability but also adventure, of caring tenderness and wild passion, of freedom and security, of familiarity and surprise. Sexual desire is stripped of its poisonous shame and self-deprecation that trickled through the cultural cracks of my childhood, stealthily und unnamed, and instead, imbued with a sacred energy. In my ideal world, sex energy is transformed into a life force that becomes fuel for the creative and the magical in us, in me and in the way I live.

My pursuit of the good things in life has lead to a great enthusiasm for flavours and cooking. It’s another type of alchemy. Here, at university, one of the many meals I shared with Nicola Fouché - lover of herbs, maker of exquisite art books, illustrator of stories, painter of emotions and grower of unconditional friendships.

4. I learned about the vital importance of relationships and friendships.

This experience has really taught me the importance of relationships. Of giving, and above all, taking. Taking from others is incredibly difficult for me because somehow, I felt, it implied that I couldn’t do things myself, that I was weak, broken, insufficient, or pitiable. But – inevitably – life has taught me the opposite: The more I was able to open myself, reveal my humanity, and to accept help from others, the deeper our connection would grow. My experience broke down protective barriers and taught me to hold my own emotions and those of others much more gracefully. Still, emotions – and living in and with them – are quite messy, there is no such thing as “handling” them, although I believe we can always learn to experience our emotional lives in a richer, more nuanced way.

I imagine our social selves like vast, glistening networks of possibilities, glued together by gooey emotion synapses, centres of shared experiences that touch us in a deeper, more archetypal way. Simple gestures can open the floodgates of emotional tenderness, strengthening these connections in a way that adds meaning to the existing and the doing we busy ourselves with here on earth.

I remember, shortly after being diagnosed with cancer, having my over-seas uncle on the phone. He asked me if I needed him to fly over to South Africa and sit by my side to hold an umbrella open above my bed to shield me. I find this powerful image of an imaginary protective umbrella so moving, startling almost, that my eyes well up at the thought every time. It’s just a fantasy, just words, but it’s a human connection that touched something deep and therefore eternal.

Since then, I have had the privilege of meeting many wonderful people all over the world, and often, these lessons of learning to show my humanness, of being unembarrassed about my shortcomings, of being unmasked, yet hopefully not brazenly impolite, have served me extremely well. Building relationships well is hard work; it’s never easy, and it’s differently defined for each individual person. But it is something I aspire to and therefore want to prioritise in my life.

2018, in my Berlin studio. For a time, not only my future in general was threatened, but also more specifically my future as a jewellery designer. I had to face the question if and how I could continue working with my hands in such an active, taxing way as is required for jewellery making. What if I survived but had to have my arm amputated? Of course, I questioned my career choice, but then doubled down pursuing it after my convalescence. Photograph by Roberto Ferraz.

5. I learned to fight cynicism and meaninglessness wherever I encounter it (including in myself).

Coming out of such an experience has truly taught me the value of meaning-making. Telling stories about ourselves, our lives, our environments and our fellow humans colours the world and justifies our existence. Telling stories shapes our own futures.

A life stripped bare of meaning and made barren with cynical snarls and nihilistic shoulder shrugs is a poor, pale, fruitless life. Often, people who have trapped themselves in a place devoid of any deeper meaning tend to fall into a type of victimhood, where life happens to them, runs over them, crushes them. Things turn sour. Others are always the lucky ones. Sometimes, the only way to respond to such a dark world is to become caught up in an inner goldrush of egotistical consuming, taking, taking, taking, because none of it will matter anyway afterwards. Other times, a response is to give up on yourself completely and surrender all responsibility. This type of person, often without meaning any harm, can suck the light and laughter and optimism from their environment, until only bitterness, scorn, resentment, complaining and ultimately despair remain. That, to me, is true hell – not death or pain or loss or grief, but the idea of losing the ability to truly live.

I want to strive to oppose this attitude wherever I find it, including in myself on sombre days, and to counter cynicism with a bright and unbridled enthusiasm for life.

The garden is both dark and light. Darkflock, a wearable fragment of that garden hand crafted from blackened sterling silver and freshwater pearls.

6. I learned o stand for the power to create meaning; to flavour life with love, light, compassion, kindness, and a quest for beauty. I learned that gardening is the ultimate metaphor for life.

To be against something is only helpful if you have something else to replace it with. To tear down a structure is a destructive act. It would be much better to grow a garden around it, until the garden has all but swallowed the structure with its winding branches and ever-evolving floral meanderings.

I see myself as a gardener of sorts; a grower of things. This reflects my view of myself and my life as a dynamic and ever-evolving process of becoming, and encompasses my interdisciplinary way of working, weaving together the fields of jewellery making, sculpture, watercolour illustration, drawing, writing and storytelling.

Gardens can be metaphors for identities too, always growing, evolving, spilling over their boundaries. The image of the garden unites the desire to organize and discipline nature – that need for clean borders – with the equally human urge to be unconstrained, free, to break through boundaries.

A garden needs tending, it needs constant attention, love and gentle curation. A garden isn’t killed if individual plants die or are cut back – on the contrary, new plants only have space to grow if old ones give way. A garden is never right or wrong, but it is simultaneously dark and light. It’s both the seen and the unseen – worlds of microbes, tiny insects and vast mycelial networks that escape our notice. In a garden, everything is connected to everything else: It’s a composition of giving and taking, an eternal cycle of birth and death, of new hopes and failed ideas, of losses and grieving and jubilant new arrivals.

Being so acutely aware of how few days I have left to live (exactly 18 253 days if I’m lucky enough to turn eighty), I want to garden my life with an intense purpose, doing it fully and wholly with my entire being, and planting seeds of light, of joy, of surprise, of kindness and of beauty.

2020. A garden is born onto the page.

February 2021. A life awaits.

It’s winter. I cherish this white and noiseless time between the bustle of our Christmas season and the start of the new year. Since moving to Europe, it’s taken me a few years to learn to fully appreciate winter. Now, I know it’s one of the reasons I wanted to move here in the first place: I needed a real winter, I needed its pause and reflection, its going-underground, its gathering-of-forces, its quiet stripping away of the unnecessairy, its gestation for new creativity to emerge.