blog

Welcome to my blog. This is a place where I think out loud, show you what I’m up to in the studio, share impressions of inspiring events or everyday moments that moved me. Some entries are carefully curated essays, others are just a few thoughts, sometimes written in English and sometimes in German.

Featured posts

newest blog entries:

Thoughts about Lichens

Thoughts about Lichens

Today, I’m reading about lichens. How they cover as much as 8% of the earth’s surface (more than is covered by tropical rain-forests), how they are ancient composite organisms made up of fungi, algae and cyanobacteria, how they can exist in the extremest conditions. Merlin Sheldrake calls them “small worlds” in his book Entagled Life - How fungi make our worlds, change our minds, and shape our futures. “Lichens are places where an organism unravels into an ecosystem and where an ecosystem congeals into an organism.”

I’m very interested in this miracle of symbiosis and collaboration, not to metion the aesthetic versatility they display. On my recent travels to South Africa, I encountered them everywhere - pink lichen growing directly on the red hard earth in the Cederberg mountain range, bright yellowish-green ones on coastal rocks, exposed to sun and Atlantic sea-spray and salt. What happens when mosses and lichen are neighbours?

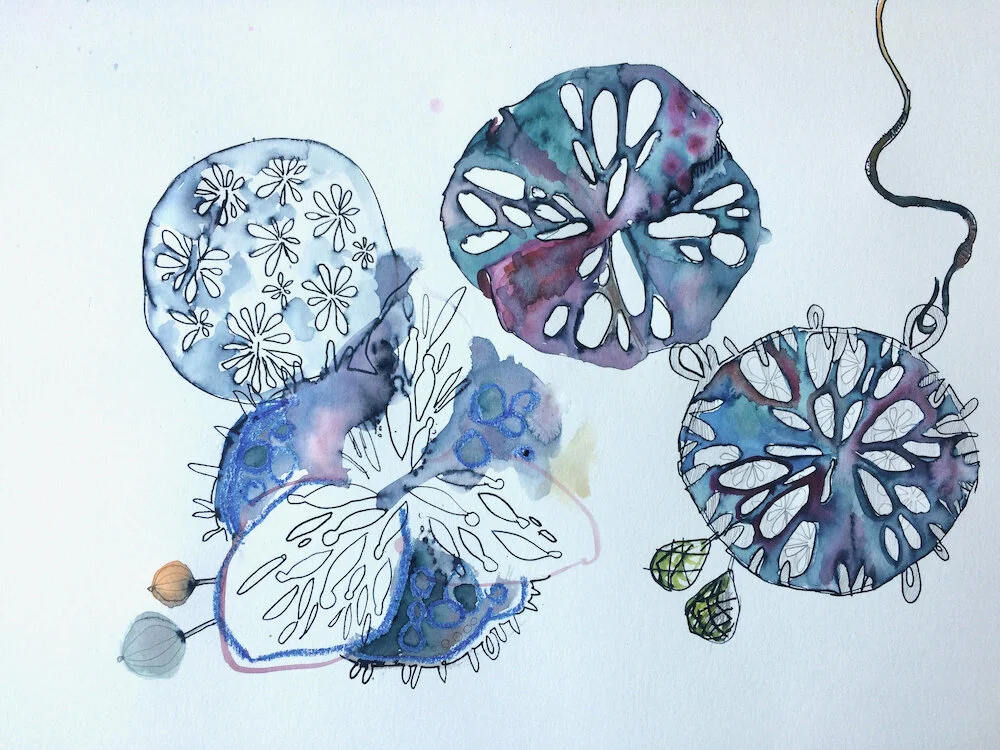

I’m thinking about how to build an impression of organisms-growing-on-other-organisms in my work, how I can play with these soft-hard surfaces, how I can use these textures, colours to create a sense of encrustation, composite beings, colonies (as you can see in my recent experiments below).

Blätterfresser

Die Blätterfresser erzählen vom tödlichen Leben, vom lebendigen Sterben. Sie erinnern daran, dass nichts ewig ist, und doch alles immer wiederkehrt. Daran, dass auch wir Narben und Fraßspuren sammeln, die oft nur den Überlebenswillen anderer Wesen auf unseren Körpern und Seelen markieren.

BlätterFresser

Die Geschichte meiner BlätterFresser/LeafEaters Kollektion.

Auf Deutsch.

Auf dem Unikampus, den ich täglich überquerte, entdeckte ich eines Tages eine Hecke mit von Insekten zerfressenen Blättern. Die löchrigen Fraßkanten bildeten ein filigranes Muster, das gleichzeitig von Leben und Tod erzählte. Manche Blätter zeigten nur ein paar verstreute Löcher wie zufällig fallen gelassene Perlen, andere waren bis auf ein Skelett abgenagt. Die Fraßspuren wurden beim längeren Hinsehen zum sich wiederholenden aber doch immer neu ausgeprägten Muster, zum Ornament.

Hier waren zwei Lebenswillen ineinander verzahnt: Ein kleines Knabberwesen auf der Suche nach Nahrung, und ein größeres Pflanzenwesen auf der Such nach Licht. Ich sah ein für unsere menschlichen Ohren stilles Drama, eine Geschichte von Geben und Nehmen und Überleben, vom Trotzen. In einer Zeit in der ich mich selber manchmal etwas un-heil fühlte, war ein Blatt, das Verletzungen wie Schmucknarben trug und doch lebte und funktionierte und photosyntierte, für mich ein starkes Symbol.

Ich schuf daraus die Kollektion Blätterfresser: Ohrringe, Broschen und Taschenglücksbringer, handgesägt aus Silber, Gold oder Kupfer, in bunt schillernden Farbtönen einzigartig emailliert. Bis heute sind viele Stücke für diese Kollektion entstanden, und jedes einzelne hat einen ganz individuellen Charakter.

Die Blätterfresser erzählen vom tödlichen Leben, vom lebendigen Sterben. Sie erinnern daran, dass nichts ewig ist, und doch alles immer wiederkehrt. Daran, dass auch wir Narben und Fraßspuren sammeln, die oft nur den Überlebenswillen anderer Wesen auf unseren Körpern und Seelen markieren.

Mit meinen hellgrünen Blätterfressern aus Gold und Emaille fühle ich mich stark. Sie erinnern daran, dass wir durch unsere löchrig gefressenen Lebensgeschichten manchmal sogar schöner, interessanter und vor allem eigener werden.

Eine Auftragsarbeit entsteht: Rote Blätterfresser als Anhänger, hier durch eine passgenaue Silberrückseite verstärkt, um das Emaille zu schützen.

Winzige fliederfarbene Blätterfresser mit Rubinen und schwarzen Süßwasserperlen auf dem Werkbrett; darüber verschiedene Arbeiten im Entstehen.

Hier eine Variante in leuchtendem Grün, verspielt und lebendig, mit facettierten Smaragdperlchen, Goldblättchen und Perlen vervollständigt.

Die von Hand gesägten Blätter werden versäubert.

Persönliche Lieblinge aus Gold und grünem Emaille, hier von Lydia Schröder fotografiert.

Das grüne Lieblingspaar auf einer Tusche- und Aquarellzeichnung.

Spätsommerliche Blätterfresser mit herbstlichem Einschlag.

Eine festlich gekleidete Trägerin mit ihren lila-rosé-bordeauxfarbenen Blätterfressern.

Das Sieb für Ängste

Ich wollte wissen, wie Angst unterm Mikroskop aussieht. Wie soll man sich Angst überhaupt vorstellen, was ist das eigentlich? Ich stellte sie mir als kleine Körner vor, die sich zusammenklumpen und sammeln, Angstkolonien bilden können. Oft, fand ich, ist die wahre Angst noch von einer schwammigen, schemenhaften Masse von Ungewissem umgeben. Eine algenartige, undurchsichtige Angst-vor-dem-Unbekannten, eine klebrige Angst-vor-der-Angst, die schwierig zu fassen ist und manchmal sogar bedrohlicher als die eigentliche Angst selbst.

Ich wollte wissen, wie Angst unterm Mikroskop aussieht. Wie soll man sich Angst überhaupt vorstellen, was ist das eigentlich? Ich stellte sie mir als kleine Körner vor, die sich zusammenklumpen und sammeln, Angstkolonien bilden können. Oft, fand ich, ist die wahre Angst noch von einer schwammigen, schemenhaften Masse von Ungewissem umgeben. Eine algenartige, undurchsichtige Angst-vor-dem-Unbekannten, eine klebrige Angst-vor-der-Angst, die schwierig zu fassen ist und manchmal sogar bedrohlicher als die eigentliche Angst selbst.

Mitten in der Pandemie merken wir umso mehr, wie diese schleimige Schlammschicht aus Ungewissheit um uns herum wächst und alles zu verschlingen droht. Die verschiedenen Ängste verschiedener Menschen geraten hier deutlich in Konflikt miteinander.

Um an den Kern der Angst zu kommen, müsste man sie irgendwie säubern, fand ich, sieben, entschlacken. Wie ein Goldwäscher, der den Schlamm geübt in sanften Kreisen ausspült, bis nur noch die glitzernden Nuggets am Boden übrig bleiben.

Dazu fertigte ich also ein Sieb für Ängste. Eines der ersten Siebe war für meine Freundin Nicola, die damals in Shanghai lebte, wo die Welt manchmal überwältigend groß und weit und bedrohlich sein konnte. Das Sieb, in filigranen Mustern handgesägt aus Silber und anschließend magisch-schillernd emailliert, lässt sich als Anhänger tragen, Talisman und Werkzeug gleichzeitig. Dieses besondere Sieb birgt einen großen, tief tannengrünen Turmalin in seinem Innern. Denn der Kern der Angst, wenn man sie entschleimt und entschlackt und von aller schmierigen Ungewissheit befreit hat, stellt sich oft als kleiner Schatz heraus. Wenn wir beispielsweise Angst davor haben, jemanden zu verlieren, bedeutet das ja, dass diese Person uns sehr wichtig ist. Angst ist also auch – manchmal – eine Kehrseite der Liebe.

Inzwischen sind einige Siebe für Ängste entstanden, manche schlicht, andere aufwändig, als Objekt, als tragbares Schmuckstück, mit Edelstein im Herzen und ohne. Die folgenden Bilder zeigen eine Reihe dieser Seelengeräte, im Entstehen und als fertige Kreationen.

Nicolas Sieb für Ängste, im Entstehen. Der Stein soll hier in Gold mit einer Krappenfassung genau an die richtige spannende Stelle platziert werden.

Hier ist bei Nicolas Sieb nun auch die emaillierte Oberseite fertig, die von der filigran handgesägten Unterseite aus Silber gehalten wird.

Nicolas Sieb für Ängste an seiner Trägerin.

Ein Sieb für Ängste als Objekt. Das Sieb selbst besteht aus unzähligen zarten Blätteröffnungen, die wie eine Verwirbelung von verstreuten Zweigen ein Muster bilden. Gerahmt wird das Sieb von einem Ring aus rosa-grauem Emaille mit Akzenten aus Rubin und schwarzen Süßwasserperlen.

Detailaufnahme. Hier sind die magischen Sprenkel der Emaillefarben zu sehen, deren geheimnisvolle Entstehung im Feuer mich so faszinieren.

Das Blättersieb im Entstehen: Hier wird als Grundlage eine Schale aus einer Scheibe Silberblech aufgetieft und anschließend planiert.

Grünes Sieb für Ängste mit geschwärzter Silberfassung.

Entwurfszeichnung in Tusche, Aquarell und Wachsstift.

Ein vollständig emailliertes Sieb für Ängste. Durchmesser der Schale ca. 13 cm.

Für jedes Sieb wird ein einzigartiges Muster von Hand ausgesägt. Dafür muss jede Öffnung erst vorgebohrt und anschließend individuell mit der Handsäge ausgestochen werden. Zuletzt werden die Öffnungen mit winzigen Feilen versäubert und entgratet - eine Arbeit, die viele Stunden in Anspruch nimmt.

Sieb mit floralem Thema aus Silber.

Enamelling in Circles

A collection of enamelled tidbits on my jewellery bench.

I’m enamelling. The kiln has heated up properly by now, and I start unpacking my enamels – little multi-coloured medicine bottles filled with glass powders in rows at the edge of my working surface. For a few moments, I simply hover over the colours, compare the different hues, delight in the subtle differences. Colours govern my life. With enamels, each one has a different personality – it is either transparent, so you can see the metal underneath after firing it, or opaque; it can be smooth or grainy, some have a high melting temperature, some a low one, some break up into bits and dissolve into other colours, some get miniature green cracks around the edges when heated a few times.

If you don’t treat them according to their personalities, they misbehave: they splinter after firing while cooling down, flake off the metal surface, become cloudy, or burn into an ugly colourless dead-looking surface.

Every action of this process of firing glass onto metal has become a strange ritual. Mixing glue for concave surfaces. Laying out brushes, spatulas, small ceramic bowls. Sifting powders onto metal. The careful, deliberate lifting and placing of the powdered pieces onto metal tripods, rickety with use and coated with stray enamel blobs. And then, opening that furnace of a kiln at 800 degrees Celsius, being bathed in a heat wave that leaves my face tingling and hot. Opening, closing, sifting, waiting, cleaning off firescale, sifting. Balancing, opening, closing, waiting, sifting, opening closing. It’s like a dance and I become entranced in it. After some time, my face becomes glowing hot and it must be bright scarlet by now. I forget about my surroundings, surrender myself willingly to the power of the enamels. Then, and only then, can they unfold their true beauty – the moment I stop trying to master them, and let them lead me. They fuse, run, melt, burn, shimmer into spectacular patterns that no-one could have foreseen. And I am left deeply satisfied by the thought that this individual pattern that just happened, right there, can never ever be reproduced again. If this is not magic, I wonder what is. To me, enamelling really isn’t a science, even though it’s a scientific process.

A kiln, glowing hot.

First layer done - one of many.

It’s no surprise that enamelling has become my favourite jewellery-making technique, considering the significance of colour in my life. Colours have their own designated meaning in my world, every cypher and every letter has its own colour in my mind, large numbers become colour sequences. However, my fascination with enamels lies deeper than just its appearance. The ancient history of the enamelling process, almost alchemical in nature before the advent of electricity, intrigues me just as much. Jewellers have used enamel for its intrinsic qualities of brightness, hardness and durability, also taking advantage of its elusiveness and mutability to suggest, among other things, precious stones, filigree inlay work, stained glass and even painting.

Although it is unclear how long enamels have existed, it is likely that they were developed in Egypt. Masters of working with fire, the Egyptians invented glass. Around the third millennium BCE they perfected the fabrication of the earliest known synthetic pigment, a double silicate of copper and calcium that compensated for the lack of affordable natural blue pigments. This new blue pigment, called Alexandrian blue, could be used in paints, inks, glass and, mixed with sodic alkaline salts, form a variety of spectacular blue faience glazes.

The development of early enamelling techniques is documented by two major sources: the Benedictine monk Theophilus whose 12th century treatise on Medieval art techniques explained some of the contemporary enamelling processes, as well as the notorious 16th century Italian jeweller Benvenuto Cellini, whose Trattato dell’Oreficeria includes detailed, step-by-step instructions on enamelling. Cellini describes the preparation of enamels as a laborious process of hand-grinding chunks of coloured, transparent glass and then washing the powder with filtered water to remove dust and impurities. Both authors describe the same kind of furnace – a type of upside-down earthenware vessel inside a protective perforated iron container, placed into a roaring fire and completely covered with hot coals. This challenging and time-consuming process can only be marvelled at, since each enamelled piece required numerous firings and timing thereof had to be impeccable.

Since enamelling was depended on pigments for its vivid colours, it is also clearly linked to alchemical practices. Much of the medieval research in chemistry was carried out by alchemists, whose laboratories and methods were described in an arcane language, often laden with metaphor. Their reluctantly and cryptically published discoveries show a wealth of experimentation focused on the transmutation of substances. Because of this interest in the mutable properties of metals, as well as their work with processes of extraction and distillation of solids and liquids, alchemists stimulated a renaissance in the production of colour pigments: they created vermilion red from sulphur and mercury, yellow by adding sulphur to arsenic, and a gold pigment by mixing sulphur, tin and mercury.

Cloisonné enamel: little pockets of colour, framed by silver or gold borders. These are cuff links I made in enamel and white gold.

Apart from this obvious, historical link, enamelling also evokes the language of alchemy: born from fire, the pale powders transform into brilliant, vitreous colour; the process is technical yet also deeply intuitive, experimental and somehow mysterious. The exact moment of perfect, glossy fusion relies on timing – in my case never governed by a neat and orderly time scale, but rather an enigmatic internal clock that relies on ‘gut feeling’ to gauge when a piece is ready. This gloriously ‘messy’, spontaneous side of the enamelling process subverts the scientific, grid-like standards that are superimposed on almost every part of modern routine.

Pale powders transform into bright, glossy glazes.

Sources:

Delamare, F & Guineau, B. 2006. Colour – Making and Using Dyes and Pigments.London: Thames & Hudson.

Strosahl, J. P. 1981. A Manual of Cloisonné & Champlevé Enamelling. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Photographs: Nicola Fouché and Nora Kovats.

Sifting pink enamel powder onto a copper earring segment.

It’s winter. I cherish this white and noiseless time between the bustle of our Christmas season and the start of the new year. Since moving to Europe, it’s taken me a few years to learn to fully appreciate winter. Now, I know it’s one of the reasons I wanted to move here in the first place: I needed a real winter, I needed its pause and reflection, its going-underground, its gathering-of-forces, its quiet stripping away of the unnecessairy, its gestation for new creativity to emerge.