blog

Welcome to my blog. This is a place where I think out loud, show you what I’m up to in the studio, share impressions of inspiring events or everyday moments that moved me. Some entries are carefully curated essays, others are just a few thoughts, sometimes written in English and sometimes in German.

Featured posts

newest blog entries:

Sea Salt & Enamels: A Teaching Experience in Murcia

An enriching teaching experience at the Escuela de Arte de Murcia in Spain.

Teaching in Murcia

A teaching experience in the South of Spain.

Written in English.

Travelling during pandemic times is difficult, if not outright impossible. Usually, my job involves a fair amount of travelling and with that, the vibrant and joyful exchange of sharing a common passion in different cultural environments.

With those pale Covid-months stretching across a barren 2020, with no exhibitions, craft fairs, symposiums, workshops and other events to participate in, I feel almost starved of the exhilarating opportunity to exit my own bubble and taste some other reality elsewhere. Travelling, and more importantly, in-person contact with other creative minds, has become so rare that its value has increased dramatically.

So, an opportunity to teach a five-day enamelling workshop at the Escuela de Arte de Murcia this past week was a welcome and precious gift. The school, which actively encourages students to travel internationally via Erasmus exchanges and offers Erasmus staff mobilities to teachers and lecturers, focusses its jewellery course on contemporary art jewellery, especially exploring alternative materials and new techniques. In the midst of our bleak and never-ending lockdown, the jewellery department reached out to me and my partner Alvaro to travel to Murcia via an Erasmus mobility grant and teach a workshop there respectively; Alvaro’s course centring around creative wax modelling techniques for casting, and mine exploring a more experimental and perhaps intuitive approach to enamelling.

The region of Murcia is situated in Southern Spain, bordering Valencia and Andalusia, with the Mediterranean Sea to the East. Travelling to this light-bathed, unknown spot of land really did something for our souls – for both of us, there was an immediate shedding of the darkness that had muted our efforts to create something wholesome and bright during the winter.

Alvaro’s workshop explored a range of different wax-working techniques, starting with several distinct kinds of modelling wax with their own unique purpose each, and becoming more experimental with the inclusion of plastic objects and organic materials, emphasising the particular preparation of dried plant parts to enable proper casting. The workshop combined all these different wax-working techniques in a final project: creating a modern chimera, an imaginary beast, a creature of all walks of life giving voice to any pluralistic interpretation the students wished to express.

My workshop expanded on basic enamelling techniques with an experimental approach, starting with easier techniques such as dry-sifting and layering enamel, and working towards more complex techniques using vitreous enamel, foil or graphite. Finally, the course encouraged participants to create completely unique and often surprising enamel effects using sand, aluminium, fine silver, organic materials to burn in the kiln, or anything else that might cause a chemical reaction with interesting results during the firing process. The students were tasked to identity and express a particular emotion in their final pieces, one that no single word exists for and that can only be described by explaining the situation it is experienced in. The spectrum of emotions presented in the end – many of them dealing with our current Covid-19-situation – revealed just how rich and varied the scope of individual experiences can be.

To teach a alongside my partner Alvaro was a unique gift in itself. Even though we both have a history of diverse teaching experiences, this was the first time for us presenting workshops side by side, being able to discuss the studio set-up, the coherence of our planned activities, and the progress of our students. There was a sense of intense, creative flow, in unison. The tapas bar nights and extended walks through the city of Murcia were filled with conversations, ideas, plans for future projects. The unbelievable food experiences here were certainly also responsible for our enthusiasm: Tomatoes that tasted of ripe sun, and perfect olives, and the most exquisite fried octopus, sea food paella, oranges that were so fresh you could smell them from across the street, and everything augmented by the most umami sea salt (which is produced in this area of Spain near Cartagena) and toppiest top quality olive oil.

We vowed to find new way to keep chasing this positive energy and vibrant life force we felt here, not to allow others with a more negative disposition to drag us down back home.

An outing on the weekend to the beautiful Ricote Valley near the city of Murcia: Alvaro in an orchard of peach trees.

We began our workshops with a presentation of our own backgrounds, our work and its philosophical underpinnings.

Alvaro explaining different wax samples and their different uses.

It was incredibly rewarding to see the students become more and more bold and experimental in their work during my workshop.

Final presentation: The students show and discuss their test plates and final pieces.

Caught mid-explanation: Although the language barrier proved to be quite a challenge, we managed to explain, describe, translate and generally communicate in the most creative way. Definitely a rewarding and mind-expanding experience.

My wonderful course of second years for this workshop: On the far right is the jewellery department’s coordinator Noelia García Gallego, on the far left Verónica, who will visit my workshop as an Erasmus intern for two months this coming summer 2021.

Our workshops were followed by a boat trip on the river, organized by the school and our kind Erasmus coordinator, Rocío. Jakaranda trees, Oleander, figs and Tipuana tipus crowded the streets and brought back tender memories from my childhood garden in South Africa.

A local fresh produce market in Murcia, where every vegetable stall seemed to have at least sixteen different types of tomato for sale.

Blätterfresser

Die Blätterfresser erzählen vom tödlichen Leben, vom lebendigen Sterben. Sie erinnern daran, dass nichts ewig ist, und doch alles immer wiederkehrt. Daran, dass auch wir Narben und Fraßspuren sammeln, die oft nur den Überlebenswillen anderer Wesen auf unseren Körpern und Seelen markieren.

BlätterFresser

Die Geschichte meiner BlätterFresser/LeafEaters Kollektion.

Auf Deutsch.

Auf dem Unikampus, den ich täglich überquerte, entdeckte ich eines Tages eine Hecke mit von Insekten zerfressenen Blättern. Die löchrigen Fraßkanten bildeten ein filigranes Muster, das gleichzeitig von Leben und Tod erzählte. Manche Blätter zeigten nur ein paar verstreute Löcher wie zufällig fallen gelassene Perlen, andere waren bis auf ein Skelett abgenagt. Die Fraßspuren wurden beim längeren Hinsehen zum sich wiederholenden aber doch immer neu ausgeprägten Muster, zum Ornament.

Hier waren zwei Lebenswillen ineinander verzahnt: Ein kleines Knabberwesen auf der Suche nach Nahrung, und ein größeres Pflanzenwesen auf der Such nach Licht. Ich sah ein für unsere menschlichen Ohren stilles Drama, eine Geschichte von Geben und Nehmen und Überleben, vom Trotzen. In einer Zeit in der ich mich selber manchmal etwas un-heil fühlte, war ein Blatt, das Verletzungen wie Schmucknarben trug und doch lebte und funktionierte und photosyntierte, für mich ein starkes Symbol.

Ich schuf daraus die Kollektion Blätterfresser: Ohrringe, Broschen und Taschenglücksbringer, handgesägt aus Silber, Gold oder Kupfer, in bunt schillernden Farbtönen einzigartig emailliert. Bis heute sind viele Stücke für diese Kollektion entstanden, und jedes einzelne hat einen ganz individuellen Charakter.

Die Blätterfresser erzählen vom tödlichen Leben, vom lebendigen Sterben. Sie erinnern daran, dass nichts ewig ist, und doch alles immer wiederkehrt. Daran, dass auch wir Narben und Fraßspuren sammeln, die oft nur den Überlebenswillen anderer Wesen auf unseren Körpern und Seelen markieren.

Mit meinen hellgrünen Blätterfressern aus Gold und Emaille fühle ich mich stark. Sie erinnern daran, dass wir durch unsere löchrig gefressenen Lebensgeschichten manchmal sogar schöner, interessanter und vor allem eigener werden.

Eine Auftragsarbeit entsteht: Rote Blätterfresser als Anhänger, hier durch eine passgenaue Silberrückseite verstärkt, um das Emaille zu schützen.

Winzige fliederfarbene Blätterfresser mit Rubinen und schwarzen Süßwasserperlen auf dem Werkbrett; darüber verschiedene Arbeiten im Entstehen.

Hier eine Variante in leuchtendem Grün, verspielt und lebendig, mit facettierten Smaragdperlchen, Goldblättchen und Perlen vervollständigt.

Die von Hand gesägten Blätter werden versäubert.

Persönliche Lieblinge aus Gold und grünem Emaille, hier von Lydia Schröder fotografiert.

Das grüne Lieblingspaar auf einer Tusche- und Aquarellzeichnung.

Spätsommerliche Blätterfresser mit herbstlichem Einschlag.

Eine festlich gekleidete Trägerin mit ihren lila-rosé-bordeauxfarbenen Blätterfressern.

Das Sieb für Ängste

Ich wollte wissen, wie Angst unterm Mikroskop aussieht. Wie soll man sich Angst überhaupt vorstellen, was ist das eigentlich? Ich stellte sie mir als kleine Körner vor, die sich zusammenklumpen und sammeln, Angstkolonien bilden können. Oft, fand ich, ist die wahre Angst noch von einer schwammigen, schemenhaften Masse von Ungewissem umgeben. Eine algenartige, undurchsichtige Angst-vor-dem-Unbekannten, eine klebrige Angst-vor-der-Angst, die schwierig zu fassen ist und manchmal sogar bedrohlicher als die eigentliche Angst selbst.

Ich wollte wissen, wie Angst unterm Mikroskop aussieht. Wie soll man sich Angst überhaupt vorstellen, was ist das eigentlich? Ich stellte sie mir als kleine Körner vor, die sich zusammenklumpen und sammeln, Angstkolonien bilden können. Oft, fand ich, ist die wahre Angst noch von einer schwammigen, schemenhaften Masse von Ungewissem umgeben. Eine algenartige, undurchsichtige Angst-vor-dem-Unbekannten, eine klebrige Angst-vor-der-Angst, die schwierig zu fassen ist und manchmal sogar bedrohlicher als die eigentliche Angst selbst.

Mitten in der Pandemie merken wir umso mehr, wie diese schleimige Schlammschicht aus Ungewissheit um uns herum wächst und alles zu verschlingen droht. Die verschiedenen Ängste verschiedener Menschen geraten hier deutlich in Konflikt miteinander.

Um an den Kern der Angst zu kommen, müsste man sie irgendwie säubern, fand ich, sieben, entschlacken. Wie ein Goldwäscher, der den Schlamm geübt in sanften Kreisen ausspült, bis nur noch die glitzernden Nuggets am Boden übrig bleiben.

Dazu fertigte ich also ein Sieb für Ängste. Eines der ersten Siebe war für meine Freundin Nicola, die damals in Shanghai lebte, wo die Welt manchmal überwältigend groß und weit und bedrohlich sein konnte. Das Sieb, in filigranen Mustern handgesägt aus Silber und anschließend magisch-schillernd emailliert, lässt sich als Anhänger tragen, Talisman und Werkzeug gleichzeitig. Dieses besondere Sieb birgt einen großen, tief tannengrünen Turmalin in seinem Innern. Denn der Kern der Angst, wenn man sie entschleimt und entschlackt und von aller schmierigen Ungewissheit befreit hat, stellt sich oft als kleiner Schatz heraus. Wenn wir beispielsweise Angst davor haben, jemanden zu verlieren, bedeutet das ja, dass diese Person uns sehr wichtig ist. Angst ist also auch – manchmal – eine Kehrseite der Liebe.

Inzwischen sind einige Siebe für Ängste entstanden, manche schlicht, andere aufwändig, als Objekt, als tragbares Schmuckstück, mit Edelstein im Herzen und ohne. Die folgenden Bilder zeigen eine Reihe dieser Seelengeräte, im Entstehen und als fertige Kreationen.

Nicolas Sieb für Ängste, im Entstehen. Der Stein soll hier in Gold mit einer Krappenfassung genau an die richtige spannende Stelle platziert werden.

Hier ist bei Nicolas Sieb nun auch die emaillierte Oberseite fertig, die von der filigran handgesägten Unterseite aus Silber gehalten wird.

Nicolas Sieb für Ängste an seiner Trägerin.

Ein Sieb für Ängste als Objekt. Das Sieb selbst besteht aus unzähligen zarten Blätteröffnungen, die wie eine Verwirbelung von verstreuten Zweigen ein Muster bilden. Gerahmt wird das Sieb von einem Ring aus rosa-grauem Emaille mit Akzenten aus Rubin und schwarzen Süßwasserperlen.

Detailaufnahme. Hier sind die magischen Sprenkel der Emaillefarben zu sehen, deren geheimnisvolle Entstehung im Feuer mich so faszinieren.

Das Blättersieb im Entstehen: Hier wird als Grundlage eine Schale aus einer Scheibe Silberblech aufgetieft und anschließend planiert.

Grünes Sieb für Ängste mit geschwärzter Silberfassung.

Entwurfszeichnung in Tusche, Aquarell und Wachsstift.

Ein vollständig emailliertes Sieb für Ängste. Durchmesser der Schale ca. 13 cm.

Für jedes Sieb wird ein einzigartiges Muster von Hand ausgesägt. Dafür muss jede Öffnung erst vorgebohrt und anschließend individuell mit der Handsäge ausgestochen werden. Zuletzt werden die Öffnungen mit winzigen Feilen versäubert und entgratet - eine Arbeit, die viele Stunden in Anspruch nimmt.

Sieb mit floralem Thema aus Silber.

An interview: Diving into infinite imaginary worlds

Recently, Klimt02, an online platform and network for contemporary jewellery, published an interview with me about my work process and sources of inspiration. It was a wonderful opportunity to rethink the way I work and re-articulate my “why” and “how” to myself in these turbulent times.

Recently, Klimt02, an online platform and network for contemporary jewellery, published an interview with me about my work process and sources of inspiration. It was a wonderful opportunity to rethink the way I work and re-articulate my “why” and “how” to myself in these turbulent times.

I thought I’d share part of the interview with you here:

1. What's local and universal in your artistic work?

Since I was raised in South Africa by a German-South African mother and a Hungarian father, I don’t just have a single identity. I have always been very aware of the fragmented, fluid way identities are built, and how important the role of one’s environment is. I can trace this thought in the way I work: there are fragments of my inspiration pointing back to so many different sources, splinters and glimpses of all the places I spent time in. I think the fact that there is this interwoven tapestry of references and inspiration in my work makes it somehow local and universal at the same time, if such a thing is possible.

There are echoes of European fairy tales and Germanic legends, but also African colours and that very South African skill of improvising in the moment; the flavour of Hungarian paprika; details of the Cape Fynbos flora; a purple Table Mountain and the aching beauty of the Wild Coast; classical double bass music; barefoot childhood memories in the vineyards; almond blossoms; hateful school uniforms; a great search for freedom and adventure. In all the visual chaos there is a search for an inner dream world, a garden that is both the origin and end, an internal fountain of inspiration, and a place to move towards.

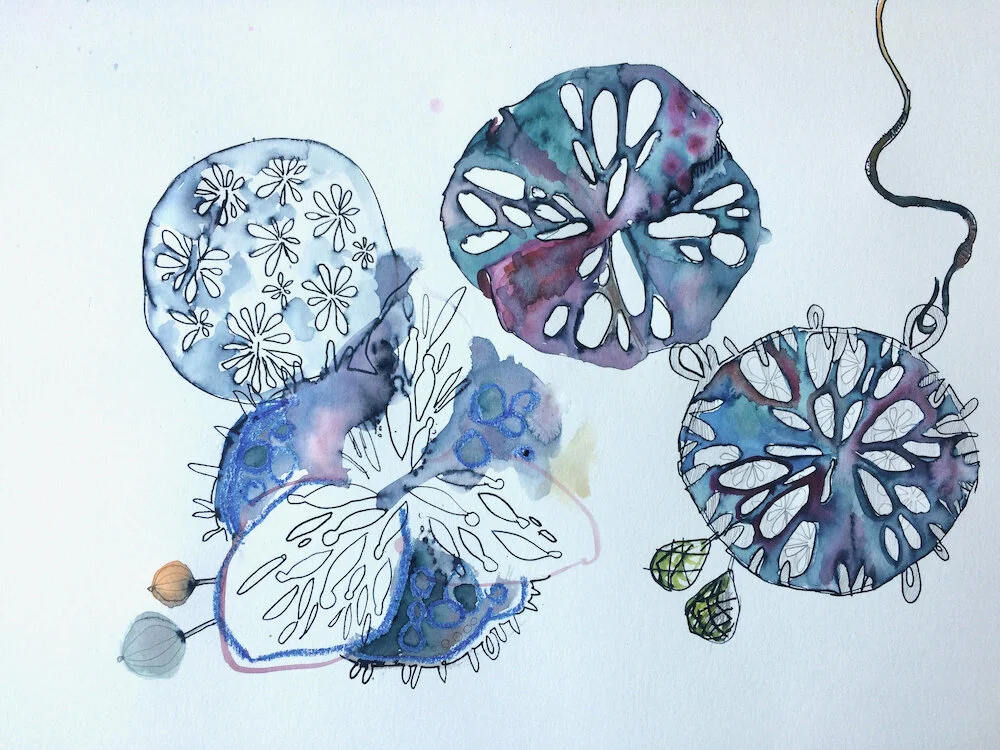

Imaginary botanical painting with watercolour, pen and drawing ink. Drawings like these are searches for new shapes and design drawings simultaneously.

2. Are there any other areas besides jewellery present in your work?

My work is completely interdisciplinary. I paint, mostly in watercolour but also in mixed media, I work in collages, I write, I make jewellery and enamelled metal objects, or strange sculptural compositions from found materials. In all these aspects of my work, I try to speak the same langue, creating a recognizable flavour of an inner Studio Nora Kovats world.

3. When you start making a new piece what is your process? How much of it is a pre-formulated plan and how much do you let the material spontaneity lead you?

My drawings are entirely spontaneous, as if I’m tapping into a wild imaginary garden inside myself, bringing out treasures to shape into compositions. This is where I first developed my visual language.

When making contemporary jewellery and metal objects, I generally have a more specific idea about the direction I am headed in. There’s a creative moment of composition where the elements are brought together, but the making of individual parts is often a very time consuming and laborious process that requires a lot of patience.

I never make just one piece at a time; it’s a creative process in several disciplines simultaneously, and I usually work on up to twenty pieces at the same time.

I mix precious and non-precious materials (such as copper, plastic, nylon and enamel in combination with gold and gemstones) and use symbolically laden resources and forms, yet aim to create something that has become precious above all because of its uniqueness – a distinctiveness born from my personal intrinsic visual language and the meticulousness of my labour. I definitely do believe that a creation of mine should strike the viewer as a precious object; however, this should be due to the skill and time invested. Because real value in this fleeting world of ours does not lie in gold or gemstones, but in human time, in devotion, passion and sincerity.

Jewellery-making offers the possibility to create entire worlds – contained miniature environments, secret spaces, autonomous ecosystems functioning in complex webs of meanings. When creating a piece, the artist pores over the small artwork in such a way that the centre of his or her world temporarily shrinks to a physical space measured in centimetres, but the metaphorical and imaginative space may be vast: a whole world of symbolism and emotion. Like with the containment of a garden in comparison to the vastness of the universe, the world in a jewellery object shrinks to a microcosm. Preciousness, usually ascribed to a range of metals and gemstones, is to some extent a quality of smallness too. A small object can be cradled in the hand; it can be more easily lost than a larger item and thus requires safe-keeping.

The size of my work is determined by several considerations: it does not consist of massive installations because of certain practical limitations, such as the size of the enamelling kiln and the extreme labour-intensity of the work; however, I also aim to evoke a sense of a miniature contained world that activates the viewer’s imagination and begs for intimate visual exploration. Smallness, of course, creates a sense of intimacy; the work displays marks of my hands on it – filing marks and hammer dents, fingerprints, perhaps even bits of my DNA and most certainly a small portion of my soul. This idea might seem overly romantic, but it embodies my personal approach to my work, conceived through the process of making.

Adding a gemstone cluster of iolite and garnet to these silver and enamel earrings to complete the composition as I imagined it in my mind.

Late-night watercolour and ink sketching inspired by a seed pod I found on one of my extended walks.

4. How important is the handmade for you in your development? What role do techniques and

technology play in your development?

Although I recognize the importance of new technological developments in general, I am a strong supporter of hand-crafted as opposed to machine-made work. I believe that we enshrine some part of ourselves within an object if we spend hours laboring over it.

My hope is that we will be moving into a time – perhaps accelerated now due to the Covid-19-crisis – where we can move away from the useless consumption of meaningless, cheaply made, trendy objects and towards a sensibility where quality, aesthetics, true craft skills and manual labour are highly valued again. Perhaps we can rise from the ashes of this upcoming severe recession as phoenixes who can forge emotional value in the form of artistic expression and express humanity in a way that creates meaning for people.

My favourite jewellery techniques include sawing out of metal, soldering to construct shapes, and enameling. My thoughts keep returning to the process of enamelling and the complete devotion it demands of its practitioner. This creative process, with its vivid possibilities of colour, its laborious ritualistic method and its ties to alchemical practices, inspires a creative drive in me that compels me to make. The making, in its quality of searching, almost becomes more important than the finished work. Making becomes a rhythmic ritual, demanding respect and reverie, as well as the need to be patiently observed, step by step, without rush. To me, the enamels are governed by their own rules, almost taking on a life of their own.

As I make, I am concerned with growing something from nothing, and with controlling that created something to a certain extent. A contradiction exists between the tight control imposed on the contained microcosm of my work, or on the enamel kiln as closed environment, and the spontaneity, impulsiveness and freedom required to permit a truly successful result – one that lives. This duality intrigues me – a constant balance between tight control and letting go. A dance. It has allowed a particular style to emerge in my work: with an emphasis placed on intuition and playfulness, I focus on growing, twisting, branching botanical shapes and vivid, unexpected colour combinations, dark and twisted as well as vibrant and playful.

Sawing stylized pomegranate shapes from a textured sheet of silver with my beloved jeweller’s saw. Here, the saw becomes an extension of my hand: a drawing tool to trace lines.

5. How important is wearability in contemporary jewellery? And in your pieces?

I think that my work changed quite a bit with regards to wearability. I used to make these crazy, spiky jewellery objects that really didn’t focus on wearability too much. They were fascinating, but rather uncomfortable to wear. As I started to earn money with my designs, my work had to be split into two distinct directions by necessity: I developed simpler, more wearable jewellery pieces such as earrings and pendants that echoed the turmoil of more intricate, entirely unwearable objects, meant to function as art in their own right.

Enamelling still life showing some of my tools like tweezers and a sieve, enamel powders and a stylized pomegranate that I am working on.

6. Which piece or job gave you more satisfaction?

There are two types of satisfaction I get in my work. Depending on my mood, I seek out either of them.

The first is a crazy, creative state of flow where I try new things, create compositions or quick sketches. This type of work flow needs a lot of momentum and energy, and although it is highly enjoyable, I cannot sustain it for too long. It’s a fast-burning, fire-like inspiration that exhausts itself after a couple of hours. This is where I create new ideas, put together final pieces, enamel pieces in quick succession or paint and draw in fast, fluid strokes.

The other is a slower, more purposeful state of meditative work, which I enjoy when I am in a more peaceful state of mind. This is where I spend hours hand-sawing intricate patterns and then finishing them off with my Swiss needle files, burnishing edges or polishing little details. Most people experience these kinds of laborious activities as frustrating or wasted time, but to me, they are essential to balance out my creative practice. It’s a space where my mind wanders, where I can listen to podcasts and audiobooks, and vaguely dream about new ideas.

7. What do you expect when you show your work to the public (for example, with an exhibition)?

I hope to open a little window into my own creative thinking, I hope to touch people emotionally and activate their imagination to develop the piece further and invent their own paradises. I love when people really take the time to look at my pieces, which are often very intricate - as if they were turning into miniature versions of themselves and going for a walk inside the sculptural shapes.

My realistic expectations at any exhibition are that many people will not understand my work or want to engage with it, but that a few viewers will stop and be drawn in by it, truly fascinated and inspired. You can’t make everybody happy, and I really don’t want to appeal everyone at once.

_

To read the interview on Klimt02, have a look here.

Work bench still life with tools and half-finished pieces. I usually work on several pieces at the same time.

Poetic Fantasy on Lost Gardens and Being Human

I miss my garden.

The last garden I had was back in 2032, that narrow walled garden at the back of our apartment. I remember walking barefoot down the stone steps, I remember birds hidden behind layers of foliage, and the taste of early summer radishes. I miss being separate but still part of the world in that tranquil microcosm.

Below is a poetic meandering of thoughts, written as an artist statement to accompany my newest series of brooches titles “Memorabilia”.

Memorabilia I. 2020. Brooch. Sterling silver (blackened), enamel on copper, steel pin, black baroque pearl. Hand sawn, constructed, enamelled.

I miss my garden.

The last garden I had was back in 2032, that narrow walled garden at the back of our apartment. I remember walking barefoot down the broad flagstones, I remember birds hidden behind layers of foliage, and the taste of early summer radishes. I miss being separate but still part of the world in that tranquil microcosm.

My garden was an inner sanctum that freed something in my chest, that carved out patterns of meaning for my life and the lives I touched. It allowed me to face the outside with courage. It was beauty, and perhaps unnecessary, although its unnecessariness made it an utter necessity in itself. It was order, and it was chaos, it was decay and love and frilliness, it was a glimpse of a splendid room that allows you to imagine the entire palace; it was a throbbing, ever-growing metaphor for our most precious human skill - the use of our imagination.

It was a space where small gestures mattered, where our humanness was reflected in a personal pantheon of fragile dreams: the furriness of moss on stone, in the twisted branch of something dry, in the post-rain puddles on the garden path.

Now that almost nothing of that mythical space remains, now that we have destroyed and scorched, wallowing in dispassionate inaction while our capacity for kindness shrivelled, while we waited, we have lost the language of imagining meaning.

We remind ourselves of our humanity in the memories that remain, held together in the blackened bone reliquaries of that sacred garden.

Memorabilia II. 2020. Brooch. Sterling silver (blackened), enamel on copper, steel pin, black baroque pearl. Hand sawn, constructed, enamelled.

Memorabilia III. 2020. Brooch. Sterling silver (blackened), enamel on silver, steel pin, black baroque pearl. Hand sawn, constructed, enamelled.

Enamelling Workshop: A glimpse

When I hosted an enamelling workshop in my Berlin studio last month, I allowed outsiders an intimate glimpse into my creative enamelling practice for the first time.

Preparation: Each participant received all necessary copper and sterling silver parts to create their own Pearlcatcher pendant.

When I hosted an enamelling workshop in my Berlin studio last month, I allowed outsiders an intimate glimpse into my creative enamelling practice for the first time. Previous workshops were always at outside locations such as the University of Stellenbosch or Studio San W in Shanghai.

The workshop included demonstrations, ample time for experiments and trials, lunch, many stories, and the completion of a variation of my Pearlcatcher pendant design. The finished piece and all experiments were the participants’ to take home, of course.

I attempted to convey – apart from my own love for colour and an enthusiasm for playful experimentation – how I feel a sense of a physical space (the studio) and a process (the act of enamelling) merging, where the doing becomes a real space in time. It’s a capsule, an entity, a ritual even, a togetherness that is caught on that day between those exact hours in that exact human setup.

Fierce heat emanating from an open enamelling kiln.

I use a solid granite slab for the hot steel tripods coming out of the kiln to cool down.

Workshop setup in the studio’s front room.

We worked with prepared enamel powders - washed and sifted - as well as small glass ornaments, blobs, and splinters that can create fascinating speckled patterns as they melt into the enamel surface.

A participant working on her first outside layer in light forget-me-not blue.

A workshop participant setting her enamelled piece into its silver setting, with a large cream-coloured pearl caught inside.

A memory of this space will capture the mood in its entire complexity – the light on a grey January afternoon, the smell of roasted lemon-pepper brussel sprouts for lunch, the heat of the enamelling kiln, the texture of sand-like enamel powders, the subtle differences in colours, the stalling of time as it is swallowed by deep concentration and effort.

A glimpse of our studio kitchen almost ready for our communal lunch, which formed part of hosting the workshop.

A scattered display of different enamelling techniques, tools and a tea tray.

I am definitely planning on repeating this experience soon, so keep an eye out for news and dates on my calendar.

The Enamel Dance

More thoughts on what it means to be enamelling.

Imaginary self-portrait as enamel dancer.

My thoughts keep returning to the process of enamelling and the complete devotion it demands of its practitioner. This creative process, with its vivid possibilities of colour, its laborious ritualistic method and its ties to alchemical practices, inspires a creative drive in me that compels me to make. The making, in its quality of searching, almost becomes more important than the finished work. Making becomes a rhythmic ritual, demanding respect and reverie, as well as the need to be patiently observed, step by step, without rush. To me, the enamels are governed by their own rules, almost taking on a life of their own.

As I make, I am concerned with growing something from nothing, and with controlling that created something to a certain extent. A contradiction exists between the tight control imposed on the contained microcosm of my work, or on the enamel kiln as closed environment, and the spontaneity, impulsiveness and freedom required to permit a truly successful result – one that lives. This duality intrigues me – a constant balance between tight control and letting go. A dance. It has allowed a particular style to emerge in my work: with an emphasis placed on intuition and playfulness, I focus on growing, twisting, branching botanical shapes and vivid, unexpected colour combinations. The garden underpins my work in every respect; however, this mythic garden in my jewellery art is vastly different from the sunny vegetable patch people grow in their back yards. The enamelled garden is dark and twisted as well as vibrant and playful.

The studio, as a small universe that is removed from ordinary space and time and severed from the ‘real’, mundane world like a magnificent imaginary garden behind walls, becomes metaphorical for the process of making. As the site for the manifestation of my own jewelled garden fantasy, the studio is transformed into a somewhat sacred space.

Enamelling in Circles

A collection of enamelled tidbits on my jewellery bench.

I’m enamelling. The kiln has heated up properly by now, and I start unpacking my enamels – little multi-coloured medicine bottles filled with glass powders in rows at the edge of my working surface. For a few moments, I simply hover over the colours, compare the different hues, delight in the subtle differences. Colours govern my life. With enamels, each one has a different personality – it is either transparent, so you can see the metal underneath after firing it, or opaque; it can be smooth or grainy, some have a high melting temperature, some a low one, some break up into bits and dissolve into other colours, some get miniature green cracks around the edges when heated a few times.

If you don’t treat them according to their personalities, they misbehave: they splinter after firing while cooling down, flake off the metal surface, become cloudy, or burn into an ugly colourless dead-looking surface.

Every action of this process of firing glass onto metal has become a strange ritual. Mixing glue for concave surfaces. Laying out brushes, spatulas, small ceramic bowls. Sifting powders onto metal. The careful, deliberate lifting and placing of the powdered pieces onto metal tripods, rickety with use and coated with stray enamel blobs. And then, opening that furnace of a kiln at 800 degrees Celsius, being bathed in a heat wave that leaves my face tingling and hot. Opening, closing, sifting, waiting, cleaning off firescale, sifting. Balancing, opening, closing, waiting, sifting, opening closing. It’s like a dance and I become entranced in it. After some time, my face becomes glowing hot and it must be bright scarlet by now. I forget about my surroundings, surrender myself willingly to the power of the enamels. Then, and only then, can they unfold their true beauty – the moment I stop trying to master them, and let them lead me. They fuse, run, melt, burn, shimmer into spectacular patterns that no-one could have foreseen. And I am left deeply satisfied by the thought that this individual pattern that just happened, right there, can never ever be reproduced again. If this is not magic, I wonder what is. To me, enamelling really isn’t a science, even though it’s a scientific process.

A kiln, glowing hot.

First layer done - one of many.

It’s no surprise that enamelling has become my favourite jewellery-making technique, considering the significance of colour in my life. Colours have their own designated meaning in my world, every cypher and every letter has its own colour in my mind, large numbers become colour sequences. However, my fascination with enamels lies deeper than just its appearance. The ancient history of the enamelling process, almost alchemical in nature before the advent of electricity, intrigues me just as much. Jewellers have used enamel for its intrinsic qualities of brightness, hardness and durability, also taking advantage of its elusiveness and mutability to suggest, among other things, precious stones, filigree inlay work, stained glass and even painting.

Although it is unclear how long enamels have existed, it is likely that they were developed in Egypt. Masters of working with fire, the Egyptians invented glass. Around the third millennium BCE they perfected the fabrication of the earliest known synthetic pigment, a double silicate of copper and calcium that compensated for the lack of affordable natural blue pigments. This new blue pigment, called Alexandrian blue, could be used in paints, inks, glass and, mixed with sodic alkaline salts, form a variety of spectacular blue faience glazes.

The development of early enamelling techniques is documented by two major sources: the Benedictine monk Theophilus whose 12th century treatise on Medieval art techniques explained some of the contemporary enamelling processes, as well as the notorious 16th century Italian jeweller Benvenuto Cellini, whose Trattato dell’Oreficeria includes detailed, step-by-step instructions on enamelling. Cellini describes the preparation of enamels as a laborious process of hand-grinding chunks of coloured, transparent glass and then washing the powder with filtered water to remove dust and impurities. Both authors describe the same kind of furnace – a type of upside-down earthenware vessel inside a protective perforated iron container, placed into a roaring fire and completely covered with hot coals. This challenging and time-consuming process can only be marvelled at, since each enamelled piece required numerous firings and timing thereof had to be impeccable.

Since enamelling was depended on pigments for its vivid colours, it is also clearly linked to alchemical practices. Much of the medieval research in chemistry was carried out by alchemists, whose laboratories and methods were described in an arcane language, often laden with metaphor. Their reluctantly and cryptically published discoveries show a wealth of experimentation focused on the transmutation of substances. Because of this interest in the mutable properties of metals, as well as their work with processes of extraction and distillation of solids and liquids, alchemists stimulated a renaissance in the production of colour pigments: they created vermilion red from sulphur and mercury, yellow by adding sulphur to arsenic, and a gold pigment by mixing sulphur, tin and mercury.

Cloisonné enamel: little pockets of colour, framed by silver or gold borders. These are cuff links I made in enamel and white gold.

Apart from this obvious, historical link, enamelling also evokes the language of alchemy: born from fire, the pale powders transform into brilliant, vitreous colour; the process is technical yet also deeply intuitive, experimental and somehow mysterious. The exact moment of perfect, glossy fusion relies on timing – in my case never governed by a neat and orderly time scale, but rather an enigmatic internal clock that relies on ‘gut feeling’ to gauge when a piece is ready. This gloriously ‘messy’, spontaneous side of the enamelling process subverts the scientific, grid-like standards that are superimposed on almost every part of modern routine.

Pale powders transform into bright, glossy glazes.

Sources:

Delamare, F & Guineau, B. 2006. Colour – Making and Using Dyes and Pigments.London: Thames & Hudson.

Strosahl, J. P. 1981. A Manual of Cloisonné & Champlevé Enamelling. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Photographs: Nicola Fouché and Nora Kovats.

Sifting pink enamel powder onto a copper earring segment.

Vlamlek

Vlamlek. 2019. Enamel, copper, sterling silver, nylon, silk, lapis lazuli, agate.

Vlamlek starts with a story about an old Cape Dutch farmhouse surrounded by Strelitzias, planted there to symbolize a protective ring of fire that was meant to shield its inhabitants from ‘foreign’ and harmful influences. This thought of barriers, of keeping out and letting in selectively, the urge to delineate the homestead, is immensely powerful and can be traced back eons in different cultures. I found myself playing with the shape and symbolism of the Strelitzia, half flame, half flower.

The Strelitzia is a peculiar flower, indigenous to South Africa yet ‘discovered’ by a British botanist and named in 1773 by Sir Joseph Banks (curator of the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew) somewhat randomly in honour of Queen Charlotte, the Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. To me, this flower epitomizes how South Africans – human, animal and botanical - have become a tangle of complex influences: the Western influence is palpable everywhere, European laws and societal norms and lately a newer but equally visible American influence, yet in between so distinctly African too, with uniquely developed customs and values, a flavour of flame and the primordial power of the earth.

Fire – heating metal and enamelling – is my language of creating. I’m becoming more experimental in my technique, savouring the burns and scars of this haphazard process. Enamel dust thrown at the metal almost violently, layer upon layer, then ground off again, scraped, colours bleeding into one another, bruised, fired over again until I achieve that mottled brightness fringed with burn. I love the immediacy of this process; I breathe it when I work. Yet it cannot be completely impulsive, there are natural laws to be obeyed, melting temperatures and properties of metals to consider, the language of the colours to respect. Enamelling is the marriage of something wild and untameable with an ordered, measured, law-abiding other.

Vlamlek is my attempt to show how, in my mind, seemingly contradictory elements have to be embraced, danced with and smelted around each other, in order to stay sane in a world where my European-South-African identity seems to tear itself apart at times.

Vlamlek (Detail).

Thoughts on Making

There is this phrase of “putting a piece of your soul” into something you are making. Sounds a little vague and clichéd to me, to be honest. So let me explore what might be meant by that a little more.

Sometimes when I create something I reach a state of existence where I am so strongly present that the importance of making transcends any other purpose of making that object. At that moment, when my gestures become precise and measured, my breathing quietens down and my thoughts become silent, when I’m focused with a deep concentration and a peculiar effortlessness at the same time, when I am uniquely present, then I know. I know that I have reached a sort of harmony that in itself is such a gift that the outcome or the finished products matter much less than the making of. Sometimes it even becomes the only thing that matters in the world, if only for an instant.

When I’m really immersed in this transcendent state, a strange feeling will start to spread, starting somewhere behind my belly button in my middle and slowly filling my entire body with a warm sense of complete and utter contentment. It’s a state so peaceful that I can literally feel the stress and anger accumulated over the day evaporate from my body.

It’s not always easy to reach this state. Usually I’m too distracted or frustrated or scattered in my mind. Thoughts of the email I forgot to write this morning or the trash that I should take out or the online shop I need to curate (never mind make stock for it) keep crowding my mind. But occasionally I do manage to hover in that strange combination of deep concentration and letting go: A focus on my gestures and the tactility of my making and the inherent laws of the material I am working with, while simultaneously letting go of the nitty-gritty worries of my life. It’s like zooming out and bringing the world into perspective – a kind of bird’s view where it becomes clear that I as an individual human being really don’t matter so much, but that I am part of a system that is wonderfully mysterious and complex and that matters a great deal. And I feel a sense of peace at not having to understand everything about this.

So making, in other words, is not so much an action taking place, it’s a state of being. A condition that reconciles seemingly paradox aspects of life (and I believe that the human mind is perfectly capable of holding several contradicting ideas simultaneously): I as an individual am so present, so focused, so important, at the centre of this process of making, and I am also dissolving into it completely, melting into my surroundings, giving myself up to breathing creativity. My personal borders become porous to let inspiration in while some part of me, some essence, can leak out into the world.

This happens especially when materials/ingredients are transformed into something more in quite a rapid way or at least at an observable pace – when you can see the making as it happens. Like drawing or painting. Enamelling. Cooking. Sawing and smithing metal. Sewing and embroidery. Writing. Making music. Even gardening. You name it. These creative endeavours all have some characteristics in common:

They are tactile and sensual experiences, where touch is extremely important – feeling the texture and surface of materials beneath your skin. Which is why writing with a pen on paper is still so fundamentally satisfying in a way that typing on a computer never can be, although there are other benefits to that.

They are immediate and transformative: With some patience you can observe how the materials you are working with change into something else you are making. You can see it grow and evolve, watch paint dry and bread dough rise deliciously and sauce thicken.

They all have one component that is mechanical and one component that is spontaneous and unpredictable; the recipe based on the maker’s knowledge and the inspiration from thin air. When I enamel, for example, I have a basic idea what I am doing and what I want to achieve, there are laws of physics I have to obey, for example melting points of enamels and metals. But some part of the process is almost magical in its unpredictability. You have no idea how the patterns will melt into each other, how the speckles of powder will form unique textures. This is the alchemy of it, the everyday mystery I choose to live with.

Without exception, creating something in this way has a positive effect on both the creator and their environment; it cleanses the world from anger and hatred, and adds self-worth, value and joy.

So yes, when you buy something hand-crafted by me, it will be an object that is steeped in my existence, in my constant state of marvel at the world and my gratitude for being alive here and now. If I could, I wouldn’t want to put a monetary price on my work. But the thought of doing anything else with my time, of earning my living in a way where I have to deny myself this creative process, is unthinkable to me.

It’s winter. I cherish this white and noiseless time between the bustle of our Christmas season and the start of the new year. Since moving to Europe, it’s taken me a few years to learn to fully appreciate winter. Now, I know it’s one of the reasons I wanted to move here in the first place: I needed a real winter, I needed its pause and reflection, its going-underground, its gathering-of-forces, its quiet stripping away of the unnecessairy, its gestation for new creativity to emerge.