blog

Welcome to my blog. This is a place where I think out loud, show you what I’m up to in the studio, share impressions of inspiring events or everyday moments that moved me. Some entries are carefully curated essays, others are just a few thoughts, sometimes written in English and sometimes in German.

Featured posts

newest blog entries:

Sea Salt & Enamels: A Teaching Experience in Murcia

An enriching teaching experience at the Escuela de Arte de Murcia in Spain.

Teaching in Murcia

A teaching experience in the South of Spain.

Written in English.

Travelling during pandemic times is difficult, if not outright impossible. Usually, my job involves a fair amount of travelling and with that, the vibrant and joyful exchange of sharing a common passion in different cultural environments.

With those pale Covid-months stretching across a barren 2020, with no exhibitions, craft fairs, symposiums, workshops and other events to participate in, I feel almost starved of the exhilarating opportunity to exit my own bubble and taste some other reality elsewhere. Travelling, and more importantly, in-person contact with other creative minds, has become so rare that its value has increased dramatically.

So, an opportunity to teach a five-day enamelling workshop at the Escuela de Arte de Murcia this past week was a welcome and precious gift. The school, which actively encourages students to travel internationally via Erasmus exchanges and offers Erasmus staff mobilities to teachers and lecturers, focusses its jewellery course on contemporary art jewellery, especially exploring alternative materials and new techniques. In the midst of our bleak and never-ending lockdown, the jewellery department reached out to me and my partner Alvaro to travel to Murcia via an Erasmus mobility grant and teach a workshop there respectively; Alvaro’s course centring around creative wax modelling techniques for casting, and mine exploring a more experimental and perhaps intuitive approach to enamelling.

The region of Murcia is situated in Southern Spain, bordering Valencia and Andalusia, with the Mediterranean Sea to the East. Travelling to this light-bathed, unknown spot of land really did something for our souls – for both of us, there was an immediate shedding of the darkness that had muted our efforts to create something wholesome and bright during the winter.

Alvaro’s workshop explored a range of different wax-working techniques, starting with several distinct kinds of modelling wax with their own unique purpose each, and becoming more experimental with the inclusion of plastic objects and organic materials, emphasising the particular preparation of dried plant parts to enable proper casting. The workshop combined all these different wax-working techniques in a final project: creating a modern chimera, an imaginary beast, a creature of all walks of life giving voice to any pluralistic interpretation the students wished to express.

My workshop expanded on basic enamelling techniques with an experimental approach, starting with easier techniques such as dry-sifting and layering enamel, and working towards more complex techniques using vitreous enamel, foil or graphite. Finally, the course encouraged participants to create completely unique and often surprising enamel effects using sand, aluminium, fine silver, organic materials to burn in the kiln, or anything else that might cause a chemical reaction with interesting results during the firing process. The students were tasked to identity and express a particular emotion in their final pieces, one that no single word exists for and that can only be described by explaining the situation it is experienced in. The spectrum of emotions presented in the end – many of them dealing with our current Covid-19-situation – revealed just how rich and varied the scope of individual experiences can be.

To teach a alongside my partner Alvaro was a unique gift in itself. Even though we both have a history of diverse teaching experiences, this was the first time for us presenting workshops side by side, being able to discuss the studio set-up, the coherence of our planned activities, and the progress of our students. There was a sense of intense, creative flow, in unison. The tapas bar nights and extended walks through the city of Murcia were filled with conversations, ideas, plans for future projects. The unbelievable food experiences here were certainly also responsible for our enthusiasm: Tomatoes that tasted of ripe sun, and perfect olives, and the most exquisite fried octopus, sea food paella, oranges that were so fresh you could smell them from across the street, and everything augmented by the most umami sea salt (which is produced in this area of Spain near Cartagena) and toppiest top quality olive oil.

We vowed to find new way to keep chasing this positive energy and vibrant life force we felt here, not to allow others with a more negative disposition to drag us down back home.

An outing on the weekend to the beautiful Ricote Valley near the city of Murcia: Alvaro in an orchard of peach trees.

We began our workshops with a presentation of our own backgrounds, our work and its philosophical underpinnings.

Alvaro explaining different wax samples and their different uses.

It was incredibly rewarding to see the students become more and more bold and experimental in their work during my workshop.

Final presentation: The students show and discuss their test plates and final pieces.

Caught mid-explanation: Although the language barrier proved to be quite a challenge, we managed to explain, describe, translate and generally communicate in the most creative way. Definitely a rewarding and mind-expanding experience.

My wonderful course of second years for this workshop: On the far right is the jewellery department’s coordinator Noelia García Gallego, on the far left Verónica, who will visit my workshop as an Erasmus intern for two months this coming summer 2021.

Our workshops were followed by a boat trip on the river, organized by the school and our kind Erasmus coordinator, Rocío. Jakaranda trees, Oleander, figs and Tipuana tipus crowded the streets and brought back tender memories from my childhood garden in South Africa.

A local fresh produce market in Murcia, where every vegetable stall seemed to have at least sixteen different types of tomato for sale.

Blätterfresser

Die Blätterfresser erzählen vom tödlichen Leben, vom lebendigen Sterben. Sie erinnern daran, dass nichts ewig ist, und doch alles immer wiederkehrt. Daran, dass auch wir Narben und Fraßspuren sammeln, die oft nur den Überlebenswillen anderer Wesen auf unseren Körpern und Seelen markieren.

BlätterFresser

Die Geschichte meiner BlätterFresser/LeafEaters Kollektion.

Auf Deutsch.

Auf dem Unikampus, den ich täglich überquerte, entdeckte ich eines Tages eine Hecke mit von Insekten zerfressenen Blättern. Die löchrigen Fraßkanten bildeten ein filigranes Muster, das gleichzeitig von Leben und Tod erzählte. Manche Blätter zeigten nur ein paar verstreute Löcher wie zufällig fallen gelassene Perlen, andere waren bis auf ein Skelett abgenagt. Die Fraßspuren wurden beim längeren Hinsehen zum sich wiederholenden aber doch immer neu ausgeprägten Muster, zum Ornament.

Hier waren zwei Lebenswillen ineinander verzahnt: Ein kleines Knabberwesen auf der Suche nach Nahrung, und ein größeres Pflanzenwesen auf der Such nach Licht. Ich sah ein für unsere menschlichen Ohren stilles Drama, eine Geschichte von Geben und Nehmen und Überleben, vom Trotzen. In einer Zeit in der ich mich selber manchmal etwas un-heil fühlte, war ein Blatt, das Verletzungen wie Schmucknarben trug und doch lebte und funktionierte und photosyntierte, für mich ein starkes Symbol.

Ich schuf daraus die Kollektion Blätterfresser: Ohrringe, Broschen und Taschenglücksbringer, handgesägt aus Silber, Gold oder Kupfer, in bunt schillernden Farbtönen einzigartig emailliert. Bis heute sind viele Stücke für diese Kollektion entstanden, und jedes einzelne hat einen ganz individuellen Charakter.

Die Blätterfresser erzählen vom tödlichen Leben, vom lebendigen Sterben. Sie erinnern daran, dass nichts ewig ist, und doch alles immer wiederkehrt. Daran, dass auch wir Narben und Fraßspuren sammeln, die oft nur den Überlebenswillen anderer Wesen auf unseren Körpern und Seelen markieren.

Mit meinen hellgrünen Blätterfressern aus Gold und Emaille fühle ich mich stark. Sie erinnern daran, dass wir durch unsere löchrig gefressenen Lebensgeschichten manchmal sogar schöner, interessanter und vor allem eigener werden.

Eine Auftragsarbeit entsteht: Rote Blätterfresser als Anhänger, hier durch eine passgenaue Silberrückseite verstärkt, um das Emaille zu schützen.

Winzige fliederfarbene Blätterfresser mit Rubinen und schwarzen Süßwasserperlen auf dem Werkbrett; darüber verschiedene Arbeiten im Entstehen.

Hier eine Variante in leuchtendem Grün, verspielt und lebendig, mit facettierten Smaragdperlchen, Goldblättchen und Perlen vervollständigt.

Die von Hand gesägten Blätter werden versäubert.

Persönliche Lieblinge aus Gold und grünem Emaille, hier von Lydia Schröder fotografiert.

Das grüne Lieblingspaar auf einer Tusche- und Aquarellzeichnung.

Spätsommerliche Blätterfresser mit herbstlichem Einschlag.

Eine festlich gekleidete Trägerin mit ihren lila-rosé-bordeauxfarbenen Blätterfressern.

Das Sieb für Ängste

Ich wollte wissen, wie Angst unterm Mikroskop aussieht. Wie soll man sich Angst überhaupt vorstellen, was ist das eigentlich? Ich stellte sie mir als kleine Körner vor, die sich zusammenklumpen und sammeln, Angstkolonien bilden können. Oft, fand ich, ist die wahre Angst noch von einer schwammigen, schemenhaften Masse von Ungewissem umgeben. Eine algenartige, undurchsichtige Angst-vor-dem-Unbekannten, eine klebrige Angst-vor-der-Angst, die schwierig zu fassen ist und manchmal sogar bedrohlicher als die eigentliche Angst selbst.

Ich wollte wissen, wie Angst unterm Mikroskop aussieht. Wie soll man sich Angst überhaupt vorstellen, was ist das eigentlich? Ich stellte sie mir als kleine Körner vor, die sich zusammenklumpen und sammeln, Angstkolonien bilden können. Oft, fand ich, ist die wahre Angst noch von einer schwammigen, schemenhaften Masse von Ungewissem umgeben. Eine algenartige, undurchsichtige Angst-vor-dem-Unbekannten, eine klebrige Angst-vor-der-Angst, die schwierig zu fassen ist und manchmal sogar bedrohlicher als die eigentliche Angst selbst.

Mitten in der Pandemie merken wir umso mehr, wie diese schleimige Schlammschicht aus Ungewissheit um uns herum wächst und alles zu verschlingen droht. Die verschiedenen Ängste verschiedener Menschen geraten hier deutlich in Konflikt miteinander.

Um an den Kern der Angst zu kommen, müsste man sie irgendwie säubern, fand ich, sieben, entschlacken. Wie ein Goldwäscher, der den Schlamm geübt in sanften Kreisen ausspült, bis nur noch die glitzernden Nuggets am Boden übrig bleiben.

Dazu fertigte ich also ein Sieb für Ängste. Eines der ersten Siebe war für meine Freundin Nicola, die damals in Shanghai lebte, wo die Welt manchmal überwältigend groß und weit und bedrohlich sein konnte. Das Sieb, in filigranen Mustern handgesägt aus Silber und anschließend magisch-schillernd emailliert, lässt sich als Anhänger tragen, Talisman und Werkzeug gleichzeitig. Dieses besondere Sieb birgt einen großen, tief tannengrünen Turmalin in seinem Innern. Denn der Kern der Angst, wenn man sie entschleimt und entschlackt und von aller schmierigen Ungewissheit befreit hat, stellt sich oft als kleiner Schatz heraus. Wenn wir beispielsweise Angst davor haben, jemanden zu verlieren, bedeutet das ja, dass diese Person uns sehr wichtig ist. Angst ist also auch – manchmal – eine Kehrseite der Liebe.

Inzwischen sind einige Siebe für Ängste entstanden, manche schlicht, andere aufwändig, als Objekt, als tragbares Schmuckstück, mit Edelstein im Herzen und ohne. Die folgenden Bilder zeigen eine Reihe dieser Seelengeräte, im Entstehen und als fertige Kreationen.

Nicolas Sieb für Ängste, im Entstehen. Der Stein soll hier in Gold mit einer Krappenfassung genau an die richtige spannende Stelle platziert werden.

Hier ist bei Nicolas Sieb nun auch die emaillierte Oberseite fertig, die von der filigran handgesägten Unterseite aus Silber gehalten wird.

Nicolas Sieb für Ängste an seiner Trägerin.

Ein Sieb für Ängste als Objekt. Das Sieb selbst besteht aus unzähligen zarten Blätteröffnungen, die wie eine Verwirbelung von verstreuten Zweigen ein Muster bilden. Gerahmt wird das Sieb von einem Ring aus rosa-grauem Emaille mit Akzenten aus Rubin und schwarzen Süßwasserperlen.

Detailaufnahme. Hier sind die magischen Sprenkel der Emaillefarben zu sehen, deren geheimnisvolle Entstehung im Feuer mich so faszinieren.

Das Blättersieb im Entstehen: Hier wird als Grundlage eine Schale aus einer Scheibe Silberblech aufgetieft und anschließend planiert.

Grünes Sieb für Ängste mit geschwärzter Silberfassung.

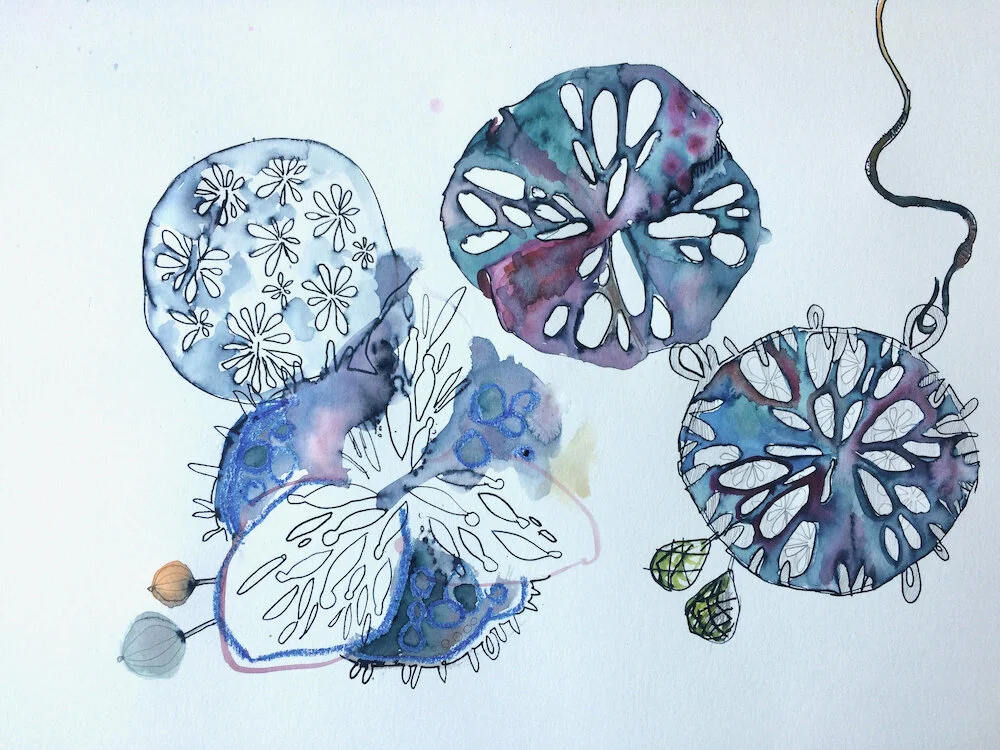

Entwurfszeichnung in Tusche, Aquarell und Wachsstift.

Ein vollständig emailliertes Sieb für Ängste. Durchmesser der Schale ca. 13 cm.

Für jedes Sieb wird ein einzigartiges Muster von Hand ausgesägt. Dafür muss jede Öffnung erst vorgebohrt und anschließend individuell mit der Handsäge ausgestochen werden. Zuletzt werden die Öffnungen mit winzigen Feilen versäubert und entgratet - eine Arbeit, die viele Stunden in Anspruch nimmt.

Sieb mit floralem Thema aus Silber.

Amphibian Living

But I have to admit: Personally, I feel a huge Munich-Jewellery-Week-shaped hole in the universe. There is something missing. What about all the energy? The field of art jewellery heavily relies on tactility, and it is incredibly difficult to fully appreciate these complex, three-dimensional art pieces on a flat screen or page - these pieces that often surprise us with a unique texture, an unexpected juxtaposition of materials that we simply can’t “get” without seeing (and sometimes touching) the real thing.

Amphibian Living

Thoughts on Munich Jewellery Week, jewellery in a digital world, and translations between spheres.

Written in English.

These past few weeks, I have been very preoccupied by thoughts about art jewellery in a digital future. How can tangible objects, made of “real” materials in the “real” world and defined by their relationship to the body, be translated into a virtual sphere? Can we have virtual bodies? And can jewellery exist on our screens and in our imaginations only?

I have no answer; these questions crowd my brain as I try to fall asleep at night, making me wonder about the future of my art and craftsmanship in a world that has been catapulted into digitalization by Covid. In Germany alone, some companies have leapt ahead five years in a only couple of months, others still send faxes and prefer to be paid in cash. This is no judgement, just a statement. Even looking at my own group of friends, colleagues and clients: Some are talking about NFTs, others refuse to utilize the internet. I believe that there is power in being fluent in the analogue as well as the digital sphere, a sort of amphibian in a changing world. It’s truly exciting to be alive in such times, feeling the shift beneath my feet.

To me, it’s also exciting to be faced with such an unknowable future – really, the only thing we can say for sure is that the future will be utterly, unimaginably different from our pasts. I don’t think we even understand how different life will be thirty years from now.

Meanwhile, Munich Jewellery Week has come and gone, the event obviously having been cancelled due to our current Covid-19 restrictions. Some institutions, groups and individuals have attempted to take the event online, hosting discussions, virtual exhibitions and talks, and distributing print magazines, most notably Current Obsession with their compendium of jewellery-related articles and editorials in this year’s Munich Jewellery Week 2021 edition.

But I have to admit: Personally, I feel a huge Munich-Jewellery-Week-shaped hole in the universe. There is something missing. What about all the energy? The field of art jewellery heavily relies on tactility, and it is incredibly difficult to fully appreciate these complex, three-dimensional art pieces on a flat screen or page - these pieces that often surprise us with a unique texture, an unexpected juxtaposition of materials that we simply can’t “get” without seeing (and sometimes touching) the real thing. More than that, these art pieces are exquisite little storytelling worlds that exude their own energy field, a mysterious force you can only feel when face to face with the piece.

I like to think that it’s not only the energy of the materiality that we feel, but the fact that it was hand made by a human being. You can detect the invisible human traces on it, the indistinct web of criss-crossing micro-movements of a highly skilled artist. It reflects the imprint of this particular artist’s visual language. Compare this to the image framed by your laptop’s silver screen (or perhaps even spiderwebbed by your broken smartphone display). While a jewellery piece is arresting and intriguing on the screen, it is not fully comprehensible in the same way.

So how can we, I wonder, learn to speak these two languages with the same fluency? How can we translate the tangible 3D into the digital? Should we even? How can makers use digital possibilities to amplify their stories, and analogue techniques to create an imprint of their being that will touch us emotionally on a level that digital art cannot? I do think we are moving into a world where neither one of these realms of being can do without the other. How can we become amphibians in this sense?

My POMEGRANATE FANTASY brooch in an imaginary orchard created by illustrator Benjamin Langford, featuring jewellery by Vika Tonu, Birgit Wimmer, Suyu Chen, Marina Voronina, Barbora Lexová, Anne Irving and Emma Rose Bennett, Geesche Arning, H2ERG, Arielle Brackett, Linsey Fontijn, Mercedes Palmer-Higgins, Dawoon Jeong, Cecilia Kesman, Idil Laslo, Mariangela Jewellery London, Zsófia Neuzer, Mayumi Okuyama, Dorothea Schippel, and Larissa Thiel.

My Otherbirthday

To say that those initial six months changed me is a gross understatement. The experience distilled my life in an instant, it filtered out a lot of bullshit. It is the single best thing that has ever happened to me in my life so far.

I think for my tenth anniversary it’s worth delving into the details of what this experience brought to life, got rid of, and how it has shaped my life for the better. Here are some of the thoughts I became aware of, as I dug deeper, and some of the learnings I took from it.

My Otherbirthday

Today I am celebrating my tenth otherbirthday. A day that’s been a silent private celebration up to now. It’s probably more important than my conception or my actual birthday, when I came into being, because out of this experience I am beginning to extract my purpose.

Written in English.

Today I am celebrating my tenth otherbirthday. A day that’s been a silent private celebration up to now. It’s probably more important than my conception or my actual birthday, when I came into being, because out of this experience I am beginning to extract my purpose. Despite its significance, I have never written about my otherbirthday in much detail publicly.

To be honest, I never had the right words to write about it. I’m not sure I have them now, but the time feels appropriate to share something so personal. We don’t only need to allow more emotion into our worlds, we need to learn to hold our emotions, those of others, to open up, and allow ourselves to be changed and weathered by our circumstances. To me, those who have lost their ability to be moved in life are somehow calcified by bitterness and disappointment, and need a good rinse of joy, like my coffee machine every couple of months.

On this day, ten years ago, I woke up in an ICU ward with no less than seven tubes stuck in my body. As I slowly drifted into consciousness, I became aware that I was incredibly thirsty; there was nothing but thirst, my world was thirst, the scratchiest sand-paper deepest desert thirst you can imagine, but I couldn’t make a single sound to cry out for water because there was a tube stuck down my throat as well.

I was edging back into a kind of awareness of my surroundings, although my vision was blurry with morphine. Ever so slowly, fragments of memory returned. I was waking up from an eight hour shoulder surgery, where an expert team of doctors had cut out my entire left shoulder joint and part of my left humerus, along with a sizeable tumour that had been growing there. They had replaced the bone with an artificial titanium shoulder joint. As I learned later, the procedure had been a little more complicated than anticipated (which was difficult enough); three separate lung emboli had forced the doctors to resuscitate me repeatedly, while I was losing grotesque amounts of blood. It must have been a serious eight-hour battle for those doctors to keep me alive, and I’m grateful to have been unconscious.

Before the operation, I had collected blood from seven different friends and family members who happened to share my blood type: Altogether 5,5 litres of that ultimate talisman, that mythical life force which I imagined flooding my body with their will-power, their strength, their tenacity, their complex love for me.

February 2011, the night of my twentieth birthday. A preciously fierce snapshot showing next to one of the kindest and most beautifully brittle souls I know, dear Louis.

About three months before, in November, just days after my last exam marking the end of my first year at university, I had been diagnosed with an aggressive, fast-growing type of bone cancer in my left shoulder joint and upper arm. An invasion of needles, medicines, poisons, facts, fears, fictions, hopes and strange odours followed. The boundaries between “good” and “bad”, and between “mine” and “not mine” dissolved quickly; the chemotherapy was good because it killed those rampant cells mercilessly, but it was also killing other fast-growing cells. “Cytotoxic,” it said on neon yellow stickers on each gelatinous bag dangling from my drip stand. I lost my hair. It didn’t matter. I lost my teen chubbiness, fifteen kilos in two months, which felt fantastic. I lost my appetite for food, my ability to concentrate, to work towards a larger goal. I lived day by day, eternally grateful for the neat slicing of time into mornings and afternoons and evenings, marked by sunrises and sunsets; a light-filled morning offers a new opportunity, every time. Was I fighting a grand fight? Was I fuelled by anger and a sort of combat-energy? Not really, no. It didn’t feel like fighting anything at all, simply because almost everything took an indescribable amount of effort. To concentrate on a book was an effort, to will myself to be interested in the interestingness of life, to watch a movie, to have a meaningful conversation. I was certainly not joy-less in that time, but filling my day with anything at all was exhausting. Everything was an act of rebellion.

It was both a time of intense aloneness, because I was living through experiences I struggled to articulate to others, and also a time of the sincerest and most intimate companionship I had ever experienced. The fragility you inhabit in such a situation allows for the greatest intimacy imaginable. When you allow others to see you in that bare, broken state, that moment of trembling weakness transforms into sheer strength: When you mobilise yourself to get up from your hospital bed for a bathroom trip, drip stand in tow, and two metres across the room transform into an arduous journey, an adventure almost, stretched over long minutes, and you let someone bear witness to that struggle. I remember feeling a new sense of precious connectivity with my mother, coming back and being a child again, being cared for with so much love, after having spread my wings at university for a year.

The operation to remove the by now grape-fruit-sized tumour was scheduled for the 11th of February. A period of convalescence followed, along with a second cluster of three rounds of chemotherapy. Since 2011, I have had another three shoulder surgeries, each improving on the previous model.

To say that those initial six months changed me is a gross understatement. The experience distilled my life in an instant, it filtered out a lot of bullshit.

It is the single best thing that has ever happened to me in my life so far.

I think for my tenth anniversary it’s worth delving into the details of what this experience brought to life, got rid of, and how it has shaped my life for the better. Here are some of the thoughts I became aware of, as I dug deeper, and some of the learnings I took from it:

2011. A snapshot at my mother’s house, one of those peaceful afternoons, about two months post-op.

1. I learned about facing my fear of pain and of death.

I believe our society (at least in predominantly Western cultures) has unlearned dealing with our own deaths well. We don’t speak about it, so the subject becomes unspeakable. We are all the more afraid of it because of its namelessness. Of course, losing someone isn’t made any less emotional if death is no longer euphemized; on the contrary. But one hopes that because the tempestuous force of death is acknowledged, one is perhaps a little better equipped to face the loss of loved ones and eventually one’s own departure.

Facing my own mortality in such a drastic way mostly killed my own fear of death. The idea of losing yourself, losing that conscious thinking inner voice, of dissolving into particles, can be absolutely terrifying. Something shifted there for me which is almost impossible to articulate. It is as if an impending sense of loneliness and lostness crystallized into a feeling of belonging and togetherness, ever so gently, a feeling of being caught, cradled, and embraced by the world, a feeling of porousness where I realize that the boundaries of my conscious self and my body might not be as real as I thought.

In my life now, I don’t evade the idea of dying, and it doesn’t make me uncomfortable anymore. Death, to me, now, will be like going home. It will happen eventually, maybe sooner or maybe later, when this journey has come to its end. And I hope that it will be okay.

For many, the fear of dying is tethered to the fear of pain. We tend to be very, very afraid of pain – with good reason from an evolutionary perspective, and we do all kinds of things to avoid pain. Yet, in my experience, our fear of pain is often much more magnified than the pain itself, once we brace ourselves.

There was pain too in my post-operation experience: The kind of incredible, breath-taking pain that really taught me how powerful my mind was, that became so much part of me that I had no idea where my body ended and the pain began. I remember the first night I was truly conscious after my operation, not being able to sleep at all, spending six hours inhaling waves of pain and releasing them out my back, making myself permeable, talking to the pain, being humbled by it and awed, imagining an endless ebb and flow, a sinus wave of pain, and eventually falling into a powerful trance where I was riding these waves triumphantly. I came to conclude that there is nothing more powerful than mastering pain; it removes most fears in life.

Childhood memories, escaping into inner worlds of infinite brightness. Watercolour and ink on paper.

2. I learned how to unearth adolescent shame, and to let it go.

What this experience really did was to eradicate my shame almost completely. To understand this, I had to delve a little deeper, further back into my growing up: My late childhood and early adolescence was profoundly marked by shame – a deep, irrational, shuddering sense of shame. Not even shame about things I did, although behaviour naturally adds another layer, but shame about the way I was. Like I had somehow become this never-good-enough, squishy disgusting thing that wasn’t worth the love and attention of others.

There is no rational explanation of this; it’s just the way I began to feel about myself around the age of 11 well until I was finishing school. I was ashamed of my un-slender body and my looks, I was ashamed of being too clumsy, too greedy, ashamed of any kind of desire I might have, ashamed of being unfashionable and ashamed of my love for fashion at the same time (secretly pouring over women’s magazines), I was ashamed of how little I knew about men and love, and at the same time afraid of being “improper” if I knew more. I was ashamed of bodily things like sneezes or teary emotional breakdowns in violin lessons, which originated from the shame of not having practised enough the week before. If someone complimented me, I would find a way of being ashamed too. It was a vicious spiral trap that sucked me into ever more ridiculous cycles of self-loathing and bouts of triumphant spitefulness. Mostly, I was also ashamed of my shame.

I found solace in literature and my school work, which was interesting and offered countless alternative worlds, and which I could excel at. Above all, I found safety in my scintillating internal world, brought to life with watercolours and inks and paintbrushes, and populated by wild and colourful characters.

After my experience of facing my mortality, my trapped-ness in that sense of shame shattered like a frozen lake bombarded with rocks. It’s difficult to untangle what exactly caused that change, but I believe it brought me to the brink of humanness, a place of utter helplessness and fragility, of inner and outer limits, a place of nakedness that does not stop at your skin level but penetrates even deeper, a place of bodily fluids and tubes in weird places and strange odours that had nothing to do with me, and at the same time, everything to do with me.

The thought of having something foreign growing within me left me in an ambivalent state where I was feeding friend and enemy cells alike with every bite I took, with every ounce of willpower I mustered. The enemy was undiscernible, it was part of me.

I believe you probably have two different options in that situation.

Either you turn on your own body, you make the entirety of it your enemy, you hate yourself, you distance yourself, you feel contaminated or dirty or broken and eventually disassociate from yourself so much that you somehow give up on yourself.

Or, and this was my story, you embrace that badness in your body. Because I was able to believe – miraculously – that none of this was my fault, I was able to learn to tolerate and live with those “evil” cancerous cells. I felt a kind of empathy for my failing immune system and my own limits, my fragility and my humanity, for my breathlessness as I was climbing stairs and for my bouts of nausea. And every bit of creative work I could do became the biggest gift. By extension, I had to embrace my entire other shadow side too. I developed a strange sense of compassion for my younger self, I wanted to go back in time and hug that poor trembling-little-bird-version of my inner self and tell her how strong and beautiful she could become. And, I learned to accept limitations in others too.

I think this attitude has made all the difference – in a much more impactful way than I could have guessed at the time. I’m not suggesting that you think away your cancer. But you have to start somewhere.

2015. A search for colour, for life, for small amulets stolen from then colourful internal paradise. Photograph of my LeafEater jewellery by Lydia Schröder.

3. I learned to search for Eros.

My desire to die well implies a desire for living well too, and this question has caused me to seek out the kind of life and the kind of relationships I want to pursue. Questions and answers around what it means to lead a meaningful life have presented themselves in turn, causing me to think, rethink and revise my life on a regular basis.

Above all, I want my life to be in search of Eros – in its full, all-encompassing original meaning: life energy and vitality in all its facets. I want to feel with all my heart, I want to dance, to fill my world with vivid colour and smiles and tears; I want flowers, I want fantastic food, music, exquisite art, I want beautiful hand-crafted things to surround me, I want books filled with secret yearnings und shadowy fantasies, I want feasts and chocolate and red shoes, I want champagne and lacy underwear. I want to be in Nature and watch her petals unfurl and flourish and decay again with the seasons. I want to see achingly beautiful sunsets on my evening walks, I want to see my paintbrush dip and twirl, I want to watch my enamels melt in glorious mottled patterns. I want to write letters to people and capture a bit of that by-gone preciousness. I want gold, and delicious deep-sea-coloured gemstones and ancient myths in my life. I want to work hard and be tired at the end of my day, I want to sweat, and laugh until my sides hurt.

With my partner, I get to pursue a precious romantic partnership where we both truly own our desire for each other: It’s a multi-faceted bouquet of love, made of stability but also adventure, of caring tenderness and wild passion, of freedom and security, of familiarity and surprise. Sexual desire is stripped of its poisonous shame and self-deprecation that trickled through the cultural cracks of my childhood, stealthily und unnamed, and instead, imbued with a sacred energy. In my ideal world, sex energy is transformed into a life force that becomes fuel for the creative and the magical in us, in me and in the way I live.

My pursuit of the good things in life has lead to a great enthusiasm for flavours and cooking. It’s another type of alchemy. Here, at university, one of the many meals I shared with Nicola Fouché - lover of herbs, maker of exquisite art books, illustrator of stories, painter of emotions and grower of unconditional friendships.

4. I learned about the vital importance of relationships and friendships.

This experience has really taught me the importance of relationships. Of giving, and above all, taking. Taking from others is incredibly difficult for me because somehow, I felt, it implied that I couldn’t do things myself, that I was weak, broken, insufficient, or pitiable. But – inevitably – life has taught me the opposite: The more I was able to open myself, reveal my humanity, and to accept help from others, the deeper our connection would grow. My experience broke down protective barriers and taught me to hold my own emotions and those of others much more gracefully. Still, emotions – and living in and with them – are quite messy, there is no such thing as “handling” them, although I believe we can always learn to experience our emotional lives in a richer, more nuanced way.

I imagine our social selves like vast, glistening networks of possibilities, glued together by gooey emotion synapses, centres of shared experiences that touch us in a deeper, more archetypal way. Simple gestures can open the floodgates of emotional tenderness, strengthening these connections in a way that adds meaning to the existing and the doing we busy ourselves with here on earth.

I remember, shortly after being diagnosed with cancer, having my over-seas uncle on the phone. He asked me if I needed him to fly over to South Africa and sit by my side to hold an umbrella open above my bed to shield me. I find this powerful image of an imaginary protective umbrella so moving, startling almost, that my eyes well up at the thought every time. It’s just a fantasy, just words, but it’s a human connection that touched something deep and therefore eternal.

Since then, I have had the privilege of meeting many wonderful people all over the world, and often, these lessons of learning to show my humanness, of being unembarrassed about my shortcomings, of being unmasked, yet hopefully not brazenly impolite, have served me extremely well. Building relationships well is hard work; it’s never easy, and it’s differently defined for each individual person. But it is something I aspire to and therefore want to prioritise in my life.

2018, in my Berlin studio. For a time, not only my future in general was threatened, but also more specifically my future as a jewellery designer. I had to face the question if and how I could continue working with my hands in such an active, taxing way as is required for jewellery making. What if I survived but had to have my arm amputated? Of course, I questioned my career choice, but then doubled down pursuing it after my convalescence. Photograph by Roberto Ferraz.

5. I learned to fight cynicism and meaninglessness wherever I encounter it (including in myself).

Coming out of such an experience has truly taught me the value of meaning-making. Telling stories about ourselves, our lives, our environments and our fellow humans colours the world and justifies our existence. Telling stories shapes our own futures.

A life stripped bare of meaning and made barren with cynical snarls and nihilistic shoulder shrugs is a poor, pale, fruitless life. Often, people who have trapped themselves in a place devoid of any deeper meaning tend to fall into a type of victimhood, where life happens to them, runs over them, crushes them. Things turn sour. Others are always the lucky ones. Sometimes, the only way to respond to such a dark world is to become caught up in an inner goldrush of egotistical consuming, taking, taking, taking, because none of it will matter anyway afterwards. Other times, a response is to give up on yourself completely and surrender all responsibility. This type of person, often without meaning any harm, can suck the light and laughter and optimism from their environment, until only bitterness, scorn, resentment, complaining and ultimately despair remain. That, to me, is true hell – not death or pain or loss or grief, but the idea of losing the ability to truly live.

I want to strive to oppose this attitude wherever I find it, including in myself on sombre days, and to counter cynicism with a bright and unbridled enthusiasm for life.

The garden is both dark and light. Darkflock, a wearable fragment of that garden hand crafted from blackened sterling silver and freshwater pearls.

6. I learned o stand for the power to create meaning; to flavour life with love, light, compassion, kindness, and a quest for beauty. I learned that gardening is the ultimate metaphor for life.

To be against something is only helpful if you have something else to replace it with. To tear down a structure is a destructive act. It would be much better to grow a garden around it, until the garden has all but swallowed the structure with its winding branches and ever-evolving floral meanderings.

I see myself as a gardener of sorts; a grower of things. This reflects my view of myself and my life as a dynamic and ever-evolving process of becoming, and encompasses my interdisciplinary way of working, weaving together the fields of jewellery making, sculpture, watercolour illustration, drawing, writing and storytelling.

Gardens can be metaphors for identities too, always growing, evolving, spilling over their boundaries. The image of the garden unites the desire to organize and discipline nature – that need for clean borders – with the equally human urge to be unconstrained, free, to break through boundaries.

A garden needs tending, it needs constant attention, love and gentle curation. A garden isn’t killed if individual plants die or are cut back – on the contrary, new plants only have space to grow if old ones give way. A garden is never right or wrong, but it is simultaneously dark and light. It’s both the seen and the unseen – worlds of microbes, tiny insects and vast mycelial networks that escape our notice. In a garden, everything is connected to everything else: It’s a composition of giving and taking, an eternal cycle of birth and death, of new hopes and failed ideas, of losses and grieving and jubilant new arrivals.

Being so acutely aware of how few days I have left to live (exactly 18 253 days if I’m lucky enough to turn eighty), I want to garden my life with an intense purpose, doing it fully and wholly with my entire being, and planting seeds of light, of joy, of surprise, of kindness and of beauty.

2020. A garden is born onto the page.

February 2021. A life awaits.

Newcomer

I’m new in town. So the natural thing for me to do is to explore, to go on long winding walks, criss-crossing the streets until I can assemble a map in my mind. Walks as long as my time and the limited daylight hours and our current lockdown curfew will permit.

Newcomer

Bamberg: I’m new in town. So the natural thing for me to do is to explore, to go on long winding walks, criss-crossing the streets until I can assemble a map in my mind.

Written in English.

I’m new in town. So the natural thing for me to do is to explore, to go on long winding walks, criss-crossing the streets until I can assemble a map in my mind. Walks as long as my time and the limited daylight hours and our current lockdown curfew will permit.

To live in a time with a government-imposed curfew! I never imagined it, it seems so bizarre. A curfew used to remind me of Second-World-War-stories, with grandmothers telling tales about blacking out windows with towels around the edges at night, stories of enemies out there, scared glances, and stealthy lovers sneaking home at night, carefully avoiding open stretches between houses. Now, we’re scared of a different enemy out there, an invisible one, all the more stealthy because we expect it in our neighbour’s friendly embrace, in our sister’s greeting and our business partner’s handshake.

I have lost myself in the narrow winding alleyways of one of Bamberg’s seven hills again, alleyways that provide barely enough space for a small waste bin, a parked (unlocked) bicycle and one human being passing by. The cobblestones are sloped towards the middle, catching puddles of ice-crusted water from yesterday’s now melting snow.

An imaginary parade of Bamberg’s oldest inhabitants, tilted in mutual support. In my mind, those remembered images of real houses from my meandering walks are fused together into imagined compositions, half fact, half fiction.

The city has a multitude of faces, that much I’ve seen already. As the winter landscape is drained of colour, and the last dregs of sunlight subside, my eyes become more attuned to these soft winter hues, micro-nuances of colour, much gentler than the glaring summer light. The eye learns to pick out and compare the most subtle differences. These are colours much too elusive, their only names might be obscure numbers on some highly technical colour chart. But how much more romantic to call the colour of the sky “swan blush” than “pantone 434M”.

These narrow streets are not as crowded as the main city centre: broad streets lined with stucco-covered historical buildings and shops. Although, even those are almost deserted now in comparison to the usual tourist bustle. There is something forlorn about these shop windows now, large posters with “SALE!!” written across them in bold red letters, “SALE 50% OFF” and “EVERYTHING NEEDS TO GO”. Some shopfronts are already empty like dark holes in the lit consumerist parade, rotten teeth. Some are dismantled, LED-signs hanging from a single wire, cardboard boxes stacked inside. Soon, the empty slot will be inhabited by another chain store.

Although, maybe not, who knows, since Bamberg’s citizens are heroically patriotic, supporting their local community businesses in ever more ingenious ways despite the national Corona restrictions. It’s a joy to watch.

To me, Bamberg features all those gloriously magical details I spent the siesta hours of my childhood discovering in gothic fairy tale books and glossy (and heavy) compilations of Romantic landscape paintings. It’s all here: The crumbling medieval houses – although the city centre is pristinely preserved and has certainly earned it’s UNESCO World Heritage status – so you have to search for those at the fringes; the moss-covered walls and stained roof tiles; the angular corners of houses unplanned and organically grown like bursts of mushrooms; the gilded church spires and patinated copper domes; the secret alleys and shortcuts; the river with its small surface twirls indicating treacherous currents underneath; the swans and waterfowl; the ancient oaks in the park that have survived wars and pandemics alike, and seem to be watching us with serious faces, branches weighed down with lichens and moss, in truth not single trees but a multitude of beings, inseparable now, tethered to their mutual network of lived history.

And the Altenburg Castle, perched on its hill above the town. Although it is neither as old nor as crumbly as some other castles in the area, it is undeniably very castle-like and quite beautiful, especially now, lit in an orange halo in the blue snow dusk. There is the forest all around, silent and loud at the same time with trees whispering, watching. There are golden sandstone walls and buildings and statues and carvings in an astounding luminous ochre the colour of golden local beer (which is plentiful), honeyed stones revealing their true splendour in the slanted sunlight.

There are so many stories layered here, dark-edged stories, stories that seep out of the mossy stones and pool black and menacingly around your feet as you pause. And there is lightness too, stories of relentless building and rebuilding, of crowning things, of preserving things, of weathering out storms and chiselling sacred knowledge into maps for future generations to rediscover.

There are cries trapped in the rough stone, burnt witches’ cries and zealous believers’ cries and shouted salutes to the Führer, cries of pain and joy, panic at the sight of the next shattering ice flood thundering down the river and tearing away bridges and houses in its path, peasant uprisings, foreign conquests, ancient ideologies. And as the brittle stones erode in our current-day tornado, I can almost watch those trapped cries escape like frozen particles in Antarctic ice melting. All those criers, I remind myself, they were all brought into this world by a mother, hopefully they were loved, and loved others in turn, they ached for safety and beauty and hoped to care for those closest to them, they grieved, they trusted in something, and they all crafted away at their intimate little dreams.

To be part of a multitude like this, and stand alone at the same time, feels infinitely powerful. I am quite excited to roam these streets until every corner is familiar, and then to watch the familiar change with the seasons, and then some more.

Altenburg Castle cushioned on its snow-topped hill above the city.

Watercolour and ink illustrations by Nora Kovats.

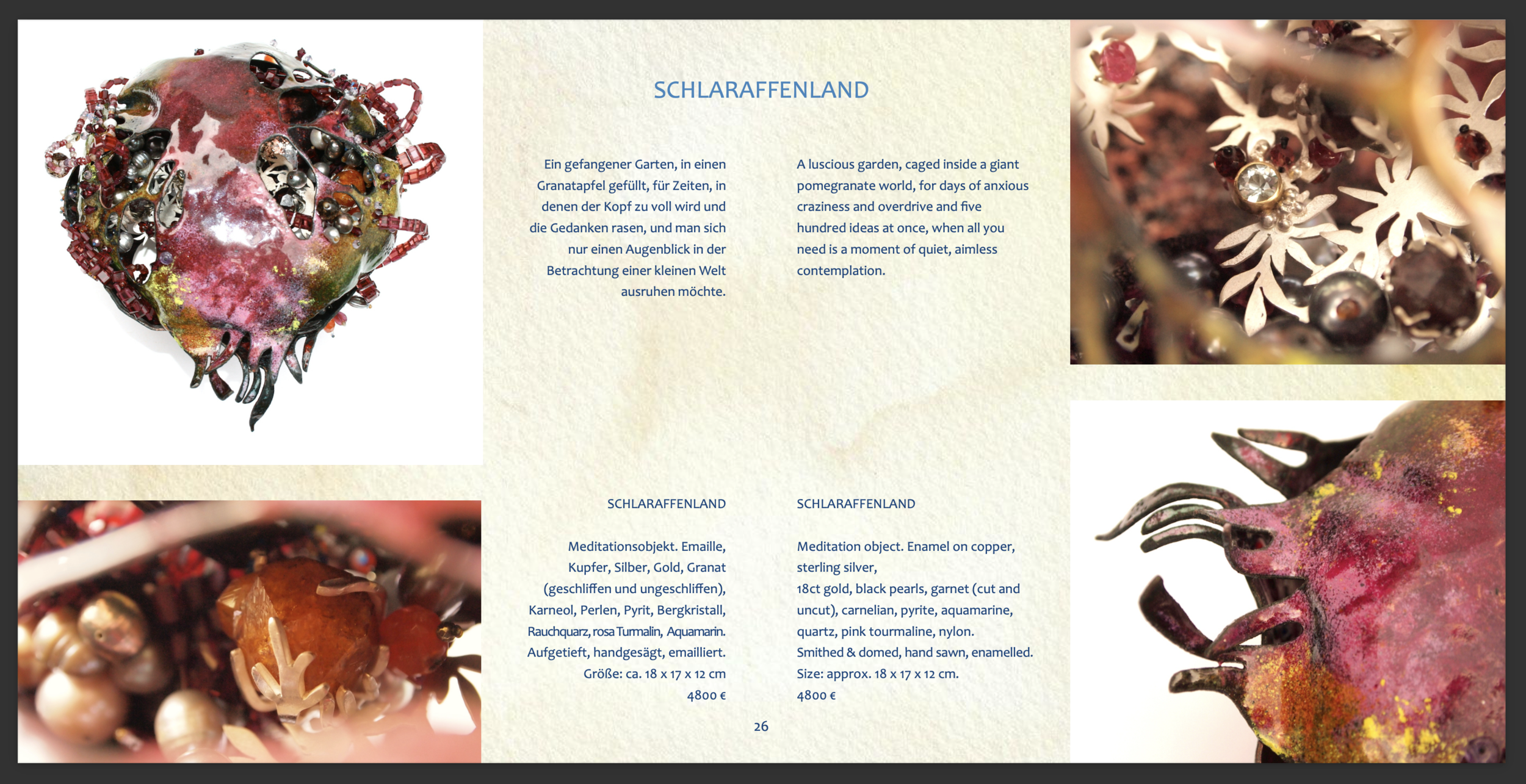

FLORILEGIUM 2020

This year, in the absence of any “real” Christmas exhibitions, I have collected my favourite pieces in a digital FLORILEGIUM to browse and explore. It is reminiscent of medieval florilegia, where poetic snippets and images where curated and collected into new compositions.

FLORILEGIUM 2020

This year, in the absence of any “real” Christmas exhibitions, I have collected my favourite pieces in a digital FLORILEGIUM to browse and explore. It is reminiscent of medieval florilegia, where poetic snippets and images where curated and collected into new compositions.

Written in English.

This year, in the absence of any “real” Christmas exhibitions, I have collected my favourite pieces in a digital FLORILEGIUM to browse and explore. It is reminiscent of medieval florilegia, where poetic snippets and images where curated and collected into new compositions.

Join me on a stroll through these past seasons, measured in the greening and browning of things, and populated with surprising encounters, botanical dreams and an eternal yearning for the perfect garden.

This collection is designed to celebrate human elegance with an edge of joyful eccentricity. Every jewellery piece is uniquely hand-crafted and one-of-a-kind. Combined with precious metals, pearls and unusual gemstones, these botanical treasures look as if they have been gathered on a dream-like journey to that internal imaginary garden.

Here is a sneak peak; the entire collection is made up of twenty-five carefully selected treasures. If you wish to view the entire document, please contact me at info@norakovats.com.

Mobilia Gallery Exhibition

Covid-19 has taught us artists and galleries to diversify our sales channels, and I am curious to see how this trend will evolve, which technologies prove to be useful and which are less helpful, which alternative methods of communication have the ability to truly touch people.

Mobilia Gallery

Exhibition titled JEWELLERY FROM ARCHITECTURE at Mobilia Gallery.

Written in English.

A small collection of my work is currently part of an exhibition at Mobilia Gallery in Cambridge, Massachusetts titled JEWELLERY FROM ARCHITECTURE. The gallery has created a delightful digital catalogue to accompany their exhibition. If you are interested to see it, please contact me or email Libby and Jo Anne directly at mobiliagallery@gmail.com. Alternatively, see the online design store Mobilia has put up on their website.

Covid-19 has taught us artists and galleries to diversify our sales channels, and I am curious to see how this trend will evolve, which technologies prove to be useful and which are less helpful, which alternative methods of communication have the ability to truly touch people. To me, it seems that the digital catalogues and online collections we are creating now also function as beautiful chronicles of the work we make, perhaps a sort of 21st century florilegium to gather and curate that which emerges from our creative practices.

Here is a screen shot of the gallery’s online display, and a selection of pieces specifically created for Mobilia Gallery:

Screen shot: Mobilia Gallery’s DESIGN STORE.

Red Closed Garden.

Pendant/Neckpiece. Vitreous enamel on copper, sterling silver (partially oxidized), orange-brown hand-stitched silk thread. Hand sawn, enamelled, fabricated.

Red Tilia.

Earrings. Vitreous enamel on copper, oxidised sterling silver hooks, black freshwater pearls, cubic zirconia drops, garnet, black nylon. Hand sawn, enamelled, fabricated, constructed.

Phoenix. Neckpiece. Vitreous enamel on copper, oxidized sterling silver clasp, silver cable, garnet, carnelian, onyx. Hand sawn, enamelled, fabricated.

Poeletjie II.

Brooch, also wearable as a pendant. Vitreous enamel on copper, sterling silver back, steel needle, faceted citrine and phrenite drops.Hand sawn, enamelled, fabricated.

Poeletjie III.

Brooch. Vitreous enamel on sterling silver, sterling silver back, steel needle, faceted phrenite drop. Hand sawn, enamelled, fabricated.

Tilia.

Earrings. Vitreous enamel on copper, sterling silver hooks, steel wire, citrine-smokey-quartz drops, peridot, pyrite, green garnet, 18 ct gold wire accents, nylon. Hand sawn, enamelled, fabricated, constructed.

Conscious Garden.

Brooch/Sculpture. Vitreous enamel on copper and sterling silver, blackened sterling silver back, steel needle, grey freshwater pearls, moss agate, and carnelian. Hand sawn, enamelled, fabricated, constructed.

Current Moods and Suffocations

Current Moods and Suffocations

On Thought-Cages and the terrible state of affairs.

Written in English.

I can feel this tightness in my chest. This is all so terribly wrong. But it’s all been wrong for a long time. In fact, I don’t know that it’s ever been right before, definitely not, but that state of perpetuity does not condone the wrong in the least.

As we are all watching the world unfurl its limbs tentatively after ducking down in the face of Covid-19, we can see it stretching in worryingly asymmetric ways. Although all have taken an unexpected hit to the gut, some countries, some people seem to be much better equipped to recover - some seem to almost carry on where they left off before this epidemic constricted daily life, commerce and our personal dreams.

Other people, other countries are left economically crippled in its wake, and with poor leaders to guide them, we can see the world rip apart even more. Certainly, almost no-one on this planet is completely unaffected by this Corona virus.

I feel a tugging worry that even the reality I used to know in my native South Africa, the place many of my family members and friends still call a home, is gliding away. My two worlds are being separated even more; a phone call with my mother sometimes leaves me saddened by the prospect of our worlds drifting apart even further, if only in the physical spaces we inhabit. Of course, engaging with another’s reality is uniquely enriching too, but it means we have fundamentally different concerns in our daily lives.

And this feeling cements the choice I have made four years ago to forge my own path in Germany for now. Perhaps to continue in our family’s peculiar pendulum legacy of switching continents every few decades: one generation, born in South Africa, moves to Europe, the next, born in Europe, moves back to South Africa. Perhaps we are each looking for the mythical country passed on to us in the stories of our parents and grandparents; be it fairy tale castles in dark enchanted forests, or vast horizons on the open savanna and sunsets behind naked desert dunes. There is a sense of charged wilderness to both, but of course, the mythical country is an oscillating Fata Morgana of our inherited memories.

How do we even begin to fight this wrongness around us, amplified by our current crisis? It’s such a crippling question, a paralysing one, too large a mountain to climb. It’s a mountain of greed: When our own reality – inflated by social pressures and responsibilities - is more real than someone else’s reality, constructs like status, lifestyle, luxury and a false sense of grandeur can be more important than another’s life. It’s a mountain of pain, of jealousy, disdain for human rights and disrespect for another’s dignity, it’s a mountain built from fear of never being good enough and of losing all, with veins of suffering seeping through its rocks like underground rivers. It’s a mountain with air so thin that it’s becoming quite difficult to breathe.

But this IS life, it’s never been different, just the types of injustices were different over time. Perhaps it’s all about a choice we make even as we and the world around us collaborate to shape our own personalities: Do we take, or do we give, primarily? Are we asking the question “what can the world offer me?”, or rather, “what can I offer the world?”?

Maybe it is our calling, as humans, to struggle against all that feels wrong, to answer the pain of the world not with anger, but with kindness and compassion, with the poetry of everyday small actions.

While this mountain feels so toweringly high, the immensity of it taking my breath away sometimes, I honestly believe I can climb a fair bit of it by noticing the small things along the path. While I kneel over a wild flower here, admire a perfectly curled infant fern over there, stop to gather small pebbles of kindness and slithers of shared stories, memories to pin into my personal herbarium, I never notice the steepness of the path I am conquering.

In my dreams, as I turn to look back, I see thousands of lived-life-fragments behind me - those most precious treasures of all. And as I look around me, I can see brothers and sisters, climbing, climbing on a thousand different paths up the mountain, climbing on, despite the fact that the precipice is tucked away in the clouds, out of sight.

Sunday Lunch Blues: Miniature Bobotie Parcels

Turmeric is a very potent pigment for painting, as well as a delicious and healthy way to spice up food.

In a fit of nostalgia and longing for some place unknown that might be the idea of home, I decided to make miniature Boboties - a traditional South African recipe that exists in a thousand different varieties. Here is my version, tucked into small phyllo pastry parcels. Perfect for small one-person portions, or finger-food at a tapas buffet.

I had tremendous fun not only making the food, but taking time to prepare ingredients and create a watercolour drawing or two on the side.

Here is a list of ingredients you will need, enough for a four-person Bobotie or plenty for a whole muffin pan. If you have any of the mixture left over, freeze it for future use.

500g mince meat (ideally a mixture of lamb and beef if you can get it)

25ml olive oil & a spoonful of butter, plus some to grease the pan

2 white & 1 red onion

2 crushed & chopped garlic cloves

a teaspoon of chopped fresh ginger

1 small grated apple

3 teaspoons of apricot jam

a slice of brown bread soaked in 125 ml beef stock

3 teaspoons curry powder

1 teaspoon turmeric

1/2 teaspoon cumin powder

1/2 teaspoon coriander pwder

salt, pepper & lemon juice to taste

phyllo pastry

250 ml milk

three large eggs

bay leaves or lime leaves to decorate

Magical colour combination.

This small bowl is made by my grandmother, Konstanze Harms, whom I had an exhibition with last year in South Africa.

First, fry the mince in a little butter and olive oil. Remove from pan.

Then chop and fry the onions, add the garlic and ginger.

Preheat oven to 180 degrees Celsius.

That smell….

Add the meat to the onion mixture, then the spices (turmeric, curry, coriander, and cumin). Grate the apple and sprinkle with lemon juice. Add that to the mixture too.

Sometimes I use whole coriander seeds as well as ground coriander - because I love the flavour so much.

Add apricot jam, and the soaked (and broken into bits) slice of bread. Finish with salt and pepper. Let everything simmer for a bit.

Traditional recipes call for raisins as well, but honestly, I hate them. Up to you!

Grease the muffin pan and layer phyllo pastry (cut into small squares with your kitchen scissors) into the individual moulds. Three to four layers of phyllo pastry are ideal. Alternatively, grease one large casserole dish.

Spoon the meat mixture into the pastry shells.

Now, for the topping, mix the eggs and the milk with a fork. Add a lot of pepper, and a little salt.

Spoon this mixture over the Bobotie parcels to create a smooth eggy layer on top. Decorate with bay leaves.

Bake in hot oven for anything between 25 and 45 minutes, depending on the size of your casserole dish or muffin pan.

Meanwhile, open a craft beer or a crisp chardonnay. Sit down and contemplate things. Do some watercolour drawing. Check your Instagram for nothing in particular. Check the oven to see whether your miniature Boboties are browning on top yet, the egg becoming all fluffy and puffed-up. Do some more drawing. Maybe, make a salad or some tomato salsa.

Bobotie is traditionally served with rice, chutney, grated coconut and sliced banana, sometimes with a finely chopped tomato and onion salad. But you don’t have to do that at all if you don’t feel like it - get creative, these are compatible with so many side dishes.

And there you go.

Enjoy! Lovely to share, and lovely to eat on your own.

Ta-daaaaa!

Spatter. Summer earrings. Enamel on sterling silver, reconstituted carved coral, freshwater pearls.

One Red Flower

Today, on an extended walk meandering through the streets of Friedrichshain in Berlin, I found a neglected, forgotten graveyard - weathered, skew headstones and completely overgrown with tree saplings and ivy. There, probably planted long ago and deciding to thrive now and here, was a bright red tulip. Solitary, blooming for nothing and no-one in particular. Just by herself. Strong and straight and true, doing her tulippy tulip thing quite formidably.

Today, on an extended walk meandering through the streets of Friedrichshain in Berlin, I found a neglected, forgotten graveyard - weathered, skew headstones and completely overgrown with tree saplings and ivy. There, probably planted long ago and deciding to thrive now and here, was a bright red tulip. Solitary, blooming for nothing and no-one in particular. Just by herself. Strong and straight and true, doing her tulippy tulip thing quite formidably.

I want to have this flower’s strength, blooming for itself and itself only, not caring a dime about other flowers being or not being around her, and giving all the more joy to passers-by because of it. Whenever I stray from that path of making art because I truly WANT to make art, I wish that moments like these would push me back to my true inner WHY.

I wish I could give all of you a bright, red flower.

Happy Earth Day!!

Finding Solitary Safe Spaces

I’ve chanced upon another safe space for my treasury. I collect them like other people collect film posters from the nineties or vintage toy cars. As far back as I remember, I’ve always had these safe spaces; as a child, they were small and cave-like, or up on my favourite climbing tree.

A magnolia tree, ancient walls, and a decorative Baroque bell tower.

The stone archways are shady and pleasantly cool after my brisk walk in the sun. They seem to swallow all sound; the outside world is shut out completely except for the cooing of pigeons in the rafters and the call of a bird that might be a hawk high above. I’m breathing the quiet air of a square church courtyard with a perfect row of sturdy rough-stone pillars forming a cloister around a fairly simple garden. A white magnolia tree in full bloom and a statue of Mother Mary balancing on a sickle moon are at its centre.

I’ve chanced upon another safe space for my treasury. I collect them like other people collect film posters from the nineties or vintage toy cars. As far back as I remember, I’ve always had these safe spaces; as a child, they were small and cave-like, or up on my favourite climbing tree. Now they tend to be wider, often on hills or high vantage points. In a world that requires so much of my energy and attention, I need them. These are spaces where I feel confident that I am enough, right now. For my own sanity, to be at peace in my body and in harmony with the world around me, I seek them out and visit them regularly. I can highly recommend this practice to all of you.

This particular courtyard belongs to a small church in Hildesheim, perched on a hill, called St. Mauritius. According to findings from archaeological excavations, it might have been a pre-Christian place of worship before the area was colonized by the Franconian Empire. St. Mauritius’ ancient Romanesque walls, built between 1058 and 1072, were added onto the foundations of an even earlier chapel commissioned by Bishop Godehard, or Gotthard of Hildesheim, in 1024. This very chapel, under the walls of St Mauritius, is the spot where the famous bishop - one of the most significant medieval Catholic saints - chose to die as he felt the end of his life approaching in 1038.

The courtyard at St. Mauritius: a simple garden of box hedges and trees.

All of these historical layers I researched only later, at home. But back in the courtyard, I was struck by a sense of presence and peace and solitude that cocooned me in cold eternal stone, despite my current (future-oriented) insecurities, and rendered my fears ludicrous. I felt invited to linger, to sit, to sit with myself and my fears and my accomplishments and my strangeness and my love and my weaknesses.

What makes a safe space safe? And I mean safe for yourself, not necessarily safe with regards to interacting with others (that’s a whole different story). I spent some time pondering this since that day on the hill at St. Mauritius. Of course, that depends on the country you are in, it depends on your personal needs and preferences, and on your intuition. But here’s what characterizes a safe space for me:

Energy

The most important attribute of a safe space is its energy. Plainly put, it needs to feel right. This is quite difficult to articulate, and if I were a physicist I’d feel confident enough to explain the complex workings of magnetic fields and electric charges to you, how they build up and, most importantly, interact, around all kinds of things made up of particles – which is literally everything around us, including us. But since I’m not, I’m simply going to say that some places have invisible charges, which we can feel and measure but not really grasp or see. I think this is what gives a place a mood, a meditative friendliness or a menacing aura, a sense of being welcomed or not. I feel safe in places with energy fields that embrace me in my imagination, beckon me, invite me to stay and wait and listen to the world.

Solitude

I feel safe in spaces where I can go alone to gather myself as a human and reassemble all the bits that have fallen into disarray. Even though I am a very social being, I recognize that my energy field is different when I am alone. Large groups of people are not conducive to the kind of contemplation you expect to find in a safe space – their energy fields would start interacting with each other, multiplying each other to create a sense of directed (at)tension. This might be wonderful at a musical concert, but less so when I want to be undisturbed.

Silence

This does not mean no sounds at all, it means the right kind of sounds, pleasant and unobtrusive sounds that allow us to listen to our own thoughts. Sounds such as birdsong, distant music, bells clanging, laughter drifting on a breeze. Away from the clutter and bustle and noisy traffic of everyday life, away from profit-hungry business dealings and the clack-clack of high heels on marble and the sound of souls drowning their own guilt and shame in productivity. Perhaps we find sounds pleasant that wake a sense of nostalgia in our depths and remind us of a mythical lost Golden Age, when things were in harmony.

Trees are these magical beings outside of human time, to me.

Agelessness

Quite often, safe spaces have an ageless, eternal feel to me, or at the very least ancient – marked by structures that have been there for generations like a thousand-year-old stone wall, or trees that might have been saplings at the time of the French Revolution (I had a tree measuring phase not too long ago, where I would measure the circumference of particularly large trees I came upon to calculate their age with a species-specific formula[1]). These structures are often something large to lean against, to lean into. Often, I find there is this sense of something so huge and incredibly ancient and unfathomable that I feel awed by it. Put in my spot as a speck in the universe, not meaningless, but just very, very tiny and rather insignificant. There is a sense of continuity, of stone walls having watched people giving birth and dying, loving and aching, over and over and over again. A feeling of solidity and stability in all this dynamic change. And a sense of belonging, despite my insignificance - a sense of owning my place in this long chain of events that is part of a larger web.

Peacefulness

Above the silence and solitude, you need to be able to actually feel safe in a space like this. There needs to be a sense of peacefulness in its truest meaning, a deep knowledge and trust in the world that no-one can come here to harm you. As if a safe space like this is also sacred, to be left clean and unsullied by malicious thoughts, so awe-inspiring that even ill-minded beings sense its sanctity and enter a kind of truce with the world here. I need this space to be so safe enough for me to dig into my own shadows and bare my own faults to myself, a space where I can be vulnerable and weak – and I can only do that if I can let down my guard in a physical sense as well. It’s difficult to find a physical safe space in countries that are collectively traumatized by crime or war.

Rhythm

Lastly, I often find that safe spaces have a kind of meditative rhythm or monotony about them, like a visual pattern of archways in regular intervals, or a sound like ocean waves crashing on rocks, the tugging of the wind at tall trees, an endless horizon, the flickering of a candle flame or open fire. We as humans have an affinity for pattern and rhythm, we like repetition because it creates a sense of harmony. It soothes us.

Ancient stones have a unique capacity to store history inside themselves, like sponges of layered meaning. There is something powerful about a road built by the Romans two millennia ago.

Of course, these traits of what makes a safe space overlap and interweave and influence each other; it’s difficult to pick them apart or discuss them individually. Often, I don’t have time to go out and actually visit a physical safe space – as might be the case with all of you in different lockdown situations now. Obviously, it’s possible to recreate these spaces in your mind.

I’ve had an imaginary safe space, my ultimate safest of all safe spaces, in my mind for years now. It’s a garden – sursprise!! – on top of an ancient stone tower, with a vast and spectacular view of an untamed and unfarmed circular horizon of hills. This place is a refuge, a source of energy, a space so intimate and private and sacred to me that I will never take anyone with me there in my process of imagining it. There are other imaginary gardens and spaces for social encounters. This is mine alone, in my very centre. A space where I can only reach on my own, which no-one could ever find, not if they could enter my mind, and not in all the parallel worlds of all universes, because I have to travel through myself to get there.

You can have your own physical and imaginary safe spaces too. A space where you recharge your batteries, where you learn to breathe until that knot in the pit of your stomach slowly unclenches. A place outside of time or space, where you sit with your vices and virtues, where you get the energy to decide to make something meaningful out of your life.

All illustrations and photographs by Nora Kovats ©.

[1] This is a great site for European trees: https://www.baumportal.de/baumalter-schaetz-o-meter.

An interview: Diving into infinite imaginary worlds

Recently, Klimt02, an online platform and network for contemporary jewellery, published an interview with me about my work process and sources of inspiration. It was a wonderful opportunity to rethink the way I work and re-articulate my “why” and “how” to myself in these turbulent times.

Recently, Klimt02, an online platform and network for contemporary jewellery, published an interview with me about my work process and sources of inspiration. It was a wonderful opportunity to rethink the way I work and re-articulate my “why” and “how” to myself in these turbulent times.

I thought I’d share part of the interview with you here:

1. What's local and universal in your artistic work?

Since I was raised in South Africa by a German-South African mother and a Hungarian father, I don’t just have a single identity. I have always been very aware of the fragmented, fluid way identities are built, and how important the role of one’s environment is. I can trace this thought in the way I work: there are fragments of my inspiration pointing back to so many different sources, splinters and glimpses of all the places I spent time in. I think the fact that there is this interwoven tapestry of references and inspiration in my work makes it somehow local and universal at the same time, if such a thing is possible.

There are echoes of European fairy tales and Germanic legends, but also African colours and that very South African skill of improvising in the moment; the flavour of Hungarian paprika; details of the Cape Fynbos flora; a purple Table Mountain and the aching beauty of the Wild Coast; classical double bass music; barefoot childhood memories in the vineyards; almond blossoms; hateful school uniforms; a great search for freedom and adventure. In all the visual chaos there is a search for an inner dream world, a garden that is both the origin and end, an internal fountain of inspiration, and a place to move towards.

Imaginary botanical painting with watercolour, pen and drawing ink. Drawings like these are searches for new shapes and design drawings simultaneously.

2. Are there any other areas besides jewellery present in your work?

My work is completely interdisciplinary. I paint, mostly in watercolour but also in mixed media, I work in collages, I write, I make jewellery and enamelled metal objects, or strange sculptural compositions from found materials. In all these aspects of my work, I try to speak the same langue, creating a recognizable flavour of an inner Studio Nora Kovats world.

3. When you start making a new piece what is your process? How much of it is a pre-formulated plan and how much do you let the material spontaneity lead you?

My drawings are entirely spontaneous, as if I’m tapping into a wild imaginary garden inside myself, bringing out treasures to shape into compositions. This is where I first developed my visual language.

When making contemporary jewellery and metal objects, I generally have a more specific idea about the direction I am headed in. There’s a creative moment of composition where the elements are brought together, but the making of individual parts is often a very time consuming and laborious process that requires a lot of patience.

I never make just one piece at a time; it’s a creative process in several disciplines simultaneously, and I usually work on up to twenty pieces at the same time.

I mix precious and non-precious materials (such as copper, plastic, nylon and enamel in combination with gold and gemstones) and use symbolically laden resources and forms, yet aim to create something that has become precious above all because of its uniqueness – a distinctiveness born from my personal intrinsic visual language and the meticulousness of my labour. I definitely do believe that a creation of mine should strike the viewer as a precious object; however, this should be due to the skill and time invested. Because real value in this fleeting world of ours does not lie in gold or gemstones, but in human time, in devotion, passion and sincerity.

Jewellery-making offers the possibility to create entire worlds – contained miniature environments, secret spaces, autonomous ecosystems functioning in complex webs of meanings. When creating a piece, the artist pores over the small artwork in such a way that the centre of his or her world temporarily shrinks to a physical space measured in centimetres, but the metaphorical and imaginative space may be vast: a whole world of symbolism and emotion. Like with the containment of a garden in comparison to the vastness of the universe, the world in a jewellery object shrinks to a microcosm. Preciousness, usually ascribed to a range of metals and gemstones, is to some extent a quality of smallness too. A small object can be cradled in the hand; it can be more easily lost than a larger item and thus requires safe-keeping.

The size of my work is determined by several considerations: it does not consist of massive installations because of certain practical limitations, such as the size of the enamelling kiln and the extreme labour-intensity of the work; however, I also aim to evoke a sense of a miniature contained world that activates the viewer’s imagination and begs for intimate visual exploration. Smallness, of course, creates a sense of intimacy; the work displays marks of my hands on it – filing marks and hammer dents, fingerprints, perhaps even bits of my DNA and most certainly a small portion of my soul. This idea might seem overly romantic, but it embodies my personal approach to my work, conceived through the process of making.

Adding a gemstone cluster of iolite and garnet to these silver and enamel earrings to complete the composition as I imagined it in my mind.

Late-night watercolour and ink sketching inspired by a seed pod I found on one of my extended walks.

4. How important is the handmade for you in your development? What role do techniques and

technology play in your development?

Although I recognize the importance of new technological developments in general, I am a strong supporter of hand-crafted as opposed to machine-made work. I believe that we enshrine some part of ourselves within an object if we spend hours laboring over it.

My hope is that we will be moving into a time – perhaps accelerated now due to the Covid-19-crisis – where we can move away from the useless consumption of meaningless, cheaply made, trendy objects and towards a sensibility where quality, aesthetics, true craft skills and manual labour are highly valued again. Perhaps we can rise from the ashes of this upcoming severe recession as phoenixes who can forge emotional value in the form of artistic expression and express humanity in a way that creates meaning for people.

My favourite jewellery techniques include sawing out of metal, soldering to construct shapes, and enameling. My thoughts keep returning to the process of enamelling and the complete devotion it demands of its practitioner. This creative process, with its vivid possibilities of colour, its laborious ritualistic method and its ties to alchemical practices, inspires a creative drive in me that compels me to make. The making, in its quality of searching, almost becomes more important than the finished work. Making becomes a rhythmic ritual, demanding respect and reverie, as well as the need to be patiently observed, step by step, without rush. To me, the enamels are governed by their own rules, almost taking on a life of their own.